0 result

The startup community and VCs are officially back from Burning Man. Summer vacations are over, football is back, and startups are officially in G.S.D. mode again. For myself, I didn’t get to do any big summer trips as I have my bachelor party later this month, and my wedding and honeymoon in December. If anyone has last minute wedding planning tips, feel free to reply back to this email or hit me up on Twitter.

I’m happy to have our friend CJ Gustafson from Mostly Metrics share another post with us. As someone who understands company financials inside and out, he’s put together a crash course on how a company looks at its books. More importantly, it’s what investors often look at when they’re deciding who to invest in.

For some of you, this is likely all new and does get pretty technical (good thing that my man CJ lays it all out in layman’s terms). But, for those of us in the startup community, I think it’s important that everyone understands these aspects of running a business. It’s not uncommon for startup employees to go out and start angel investing or found their own companies — we likely all know a few who have done it. If you want to be one of those people, these are crucial concepts to nail down.

OK, here goes CJ.

🏃 We had a good run, right? It appears we’ve turned the page on the days of limited due diligence and growth at all costs. The next chapter in fundraising seems to be characterized by a reversion to the mean of sorts.

I had an epiphany last week — there’s a whole cohort of high-flying startups (at least from a valuation perspective) who have never raised in “normal” times. Multiple companies raised multiple rounds during the pandemic, and received credit for one, two, and MAYBE even three years out in (forecasted / probably / hopefully) revenue growth. They were the beneficiaries of a test that was only looking for one answer: revenue growth.

The companies taking these deals shouldn't really be blamed. It’s usually in management’s best interest to take the cash, put it in the bank, and save it for a rainy day (like, well, the last six months).

There will be a lot of companies that do amazing things with the cash they raised during COVID. They’ve gassed up the car for the long haul and won’t need a pitstop for a while. There will also be some companies that treat the cash like ticker tape at the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

Companies have been asked to revise their operating models to show not just revenue growth, but also operational leverage.

In other words, it’s time to dust off the old playbook, sharpen our pencils, and revisit what investors pay for in normal times.

Let’s look closer at each of these components to understand their drivers and how to optimize for an attractive financial profile.

Bear with me as I do get pretty specific on all these terms, but my goal is to help demystify what financial teams are looking at on a daily basis .

You’re worth more the longer you can gobble up market share. Valuation hits a plateau when revenue growth slows. So, the size of your market matters.

How big is the pond you are fishing in? And how many fish can you realistically catch?

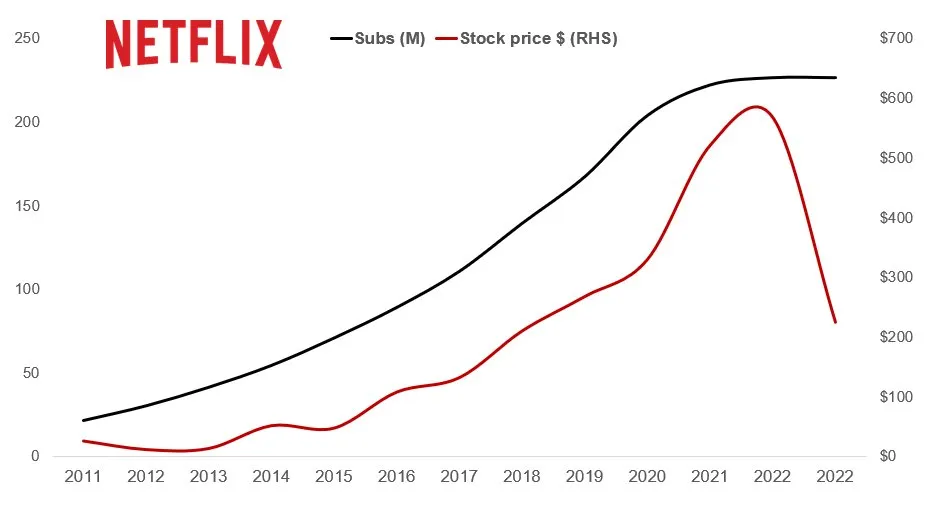

Netflix is a great example because they did the unthinkable: they sold pretty much everyone in the world a subscription.In other words, they’ve almost completely penetrated their TAM.

Check out this freakishly sad graph of Netflix’s stock price when their user growth went horizontal. Valuation dropped precipitously from $300B to $100B.

Takeaway: Much like a running back in the NFL, you don’t get paid for what you’ve done in the past. You’re being paid for how many yards you have left in your legs.

Here’s what goes into long-term revenue growth potential:

💸 Recurring revenue. Investors hate uncertainty (it’s a major reason the markets are acting the way they are this year). When revenue is contractually locked in, it takes a lot of angst off the table.

The more you can de-risk your future revenue — whether that be through ironclad multi-year subscription contracts or pre-paid usage-based commitments — investors will reward you for a clearer line of sight.

It’s also easier to plan for the rest of your financial profile when you know, to a degree, what to expect coming through the front doors.

Takeaway: Predictability is valuable for a multitude of reasons.

Dollar retention. It’s much cheaper to retain an existing customer than go out and acquire a new one.

Takeaway: The easiest path to revenue is the customer you’ve already got.

Let’s make our way down the P&L (profit and losses) for this series. Again, some of these get pretty technical, so I break these terms down into their basic elements.

🪙 Gross profit margin: Gross profit is revenue subtracted from the cost of service. Additionally, gross margin is the same as gross profit as a percentage of revenue.

Takeaway: There’s a generous flywheel effect at play here: higher GM leads to more cash to invest, which leads to more revenue, which leads to more GM…

✉️ Sales and marketing costs: OK, now we’re in the middle of the P&L. Let’s dig into OpEx (operating expenses. How expensive is it for you to go out and acquire net new customers?

Takeaway: Go-t- market models with built-in leverage are rewarded more handsomely in their valuations. Look to product-ed growth teams at DataDog (where the product, in essence, can sell itself) or high velocity inside sales teams at Cloudflare.

🗒️ Net income margin: We’re now at the bottom of the P&L. Net income is what’s left over at the end of the day to invest back into the business, buy back shares, or pay out to shareholders in the form of fat dividends.

Takeaway: Net income margin equates to optionality and, often, freedom.

🗂️ To sum it up:, investors pay for where your business is going and what it’s made of. You can go further and faster if you are built the right way. For the last two or three years, many have only focused on how fast a business could go in one direction.

It’s also very important to note that the world isn’t collapsing after what was, basically, a massive free-for-all with very few downsides. So,we’re really just returning to to an investment, and economic, environment that’s closer to the historic norm.. That’s to say: right now isn’t the anomaly, it was actually the last few years of sky-high valuations and never-ending cash raises. But it is fair to ask: Did the pendulum swing a bit too far the other way? Probably. And, hopefully, it levels out within the next year.

Many VC’s took the summer off after many had a FOMO-centric investment philosophy during the past economic cycle. And some decided to turn the page on 2022 entirely.

The word on the street is that there will be some fundraising splashes this fall. There is still a lot of cash on the borderlines, anxiously waiting to make the migration into the bank accounts of innovative founders. This time around, though, the test will be more comprehensive, and we have to remember what investors are willing to pay for in a normal market.

Things we’re digging