If you work for a tech startup or pre-IPO company, it’s likely you’ve been granted incentive stock options (ISOs).

Hopefully, they’ll make you money someday. But how much you’ll make depends for a good part on how they’re taxed.

It isn’t easy to educate yourself on this.

Most info isn’t specific to the tech startup situation. Or it’s written in jargonese. Or it’s too high-level to be practically useful.

That’s why we put together this guide:

An in-depth resource on ISO taxes and strategies — written in plain English — with helpful visualizations.

Still have questions? Feel free to hit us up for a chat in the bottom right. ↘️

Note: this guide is complete, but a little simplified

ISO taxation is a rabbit hole of complexity – mainly because of the alternative minimum tax (AMT).

The page you're on now fully explains ISO taxation, but we've simplified the part about AMT.

That means you'll get the key takeaways, but you won't grasp why it works like this – and there will be some edge cases that this explanation won't cover.

For most startup employees, that will be more than enough.

But if you're the type of person who doesn't want to cut any corners, we'll show you how deep the rabbit hole goes. Enjoy 🐰

TL;DR

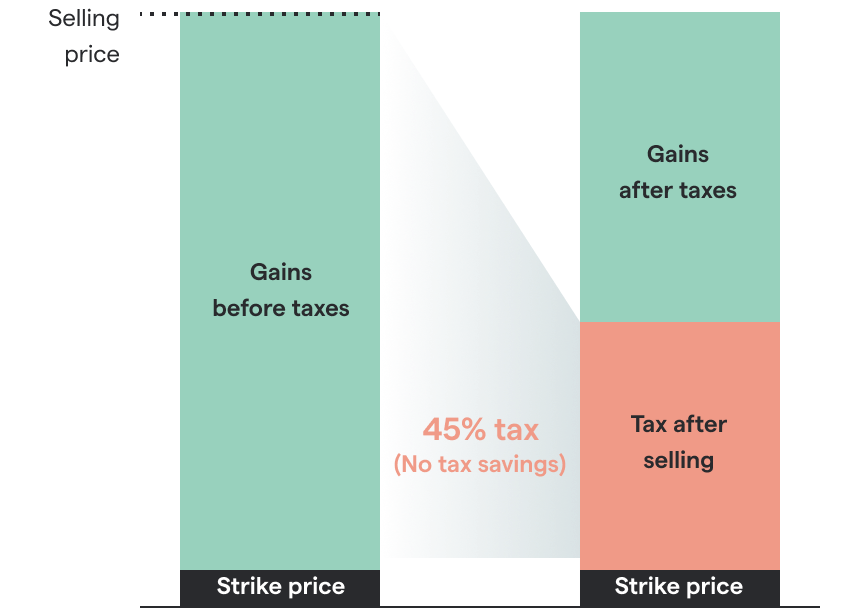

If your company exits and you sell your ISOs, the money you make is taxed.

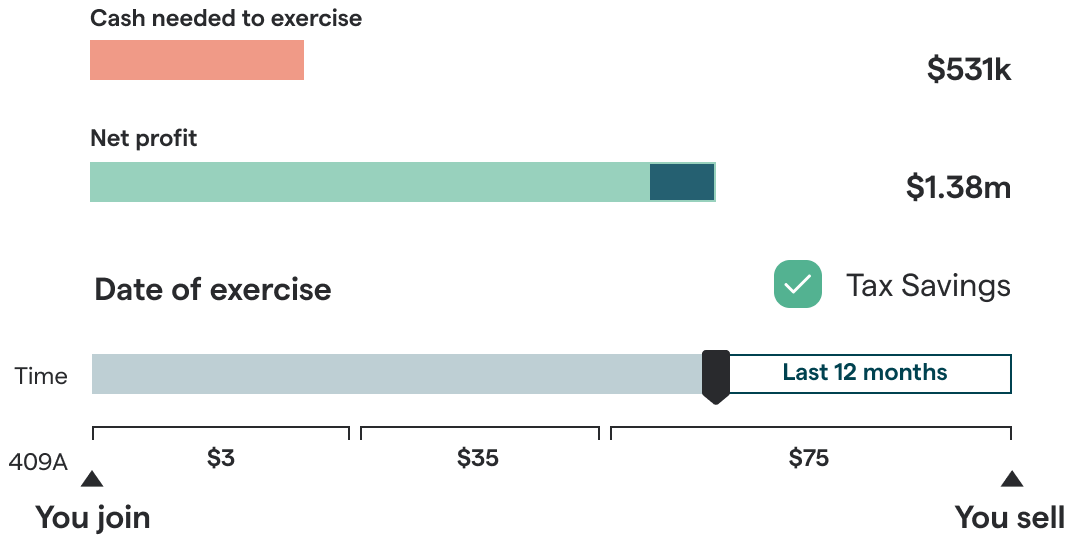

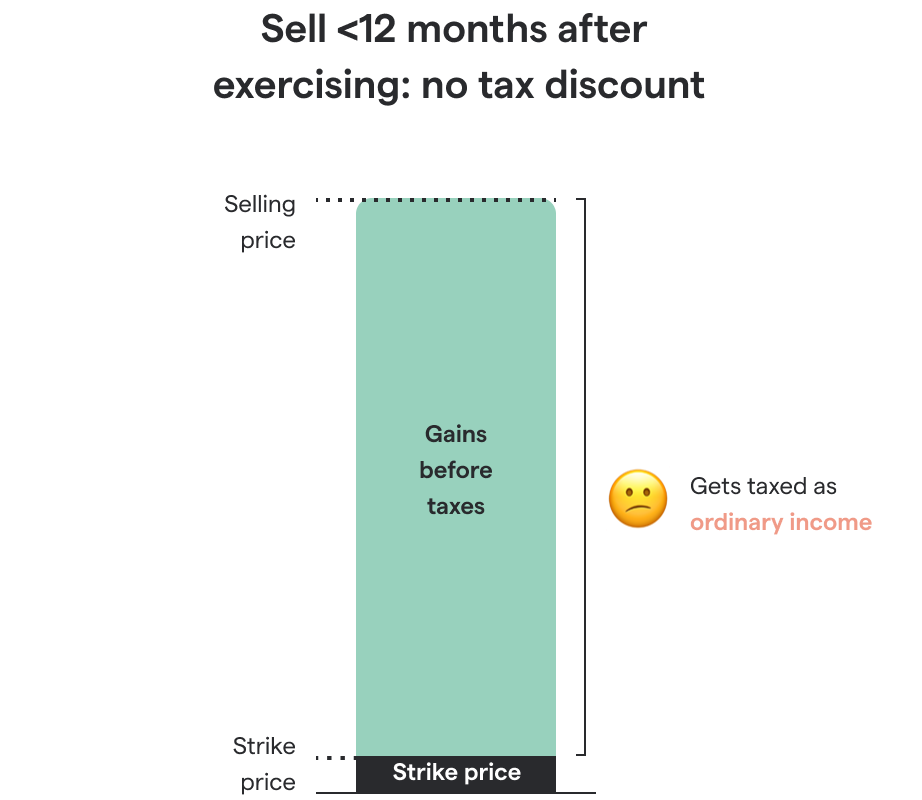

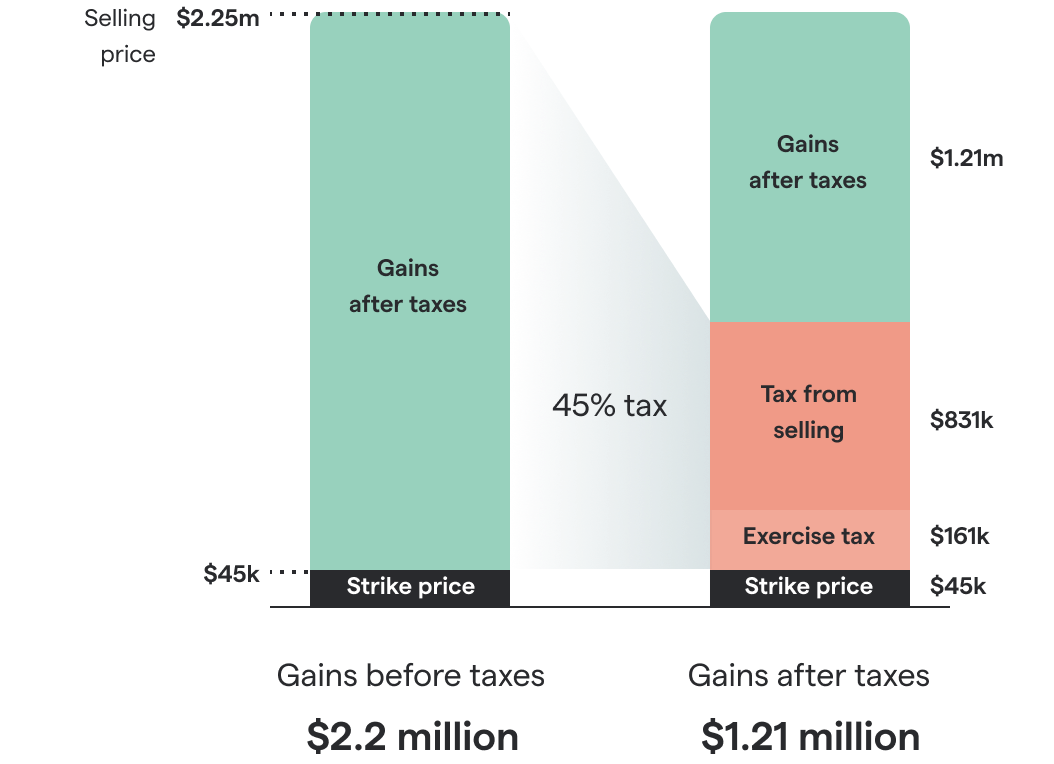

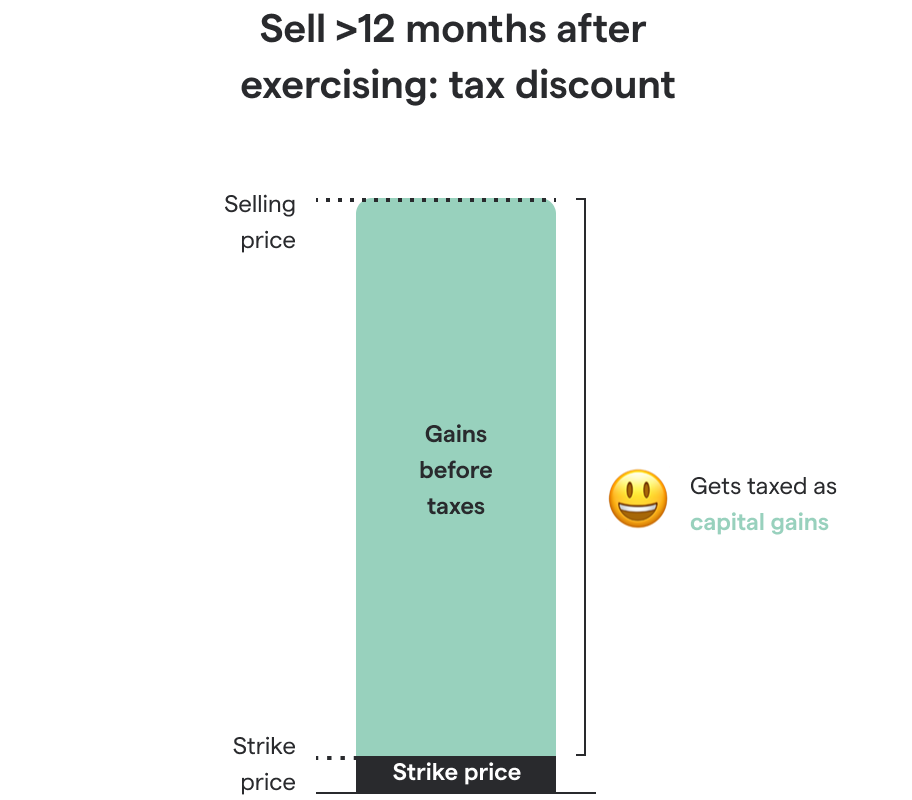

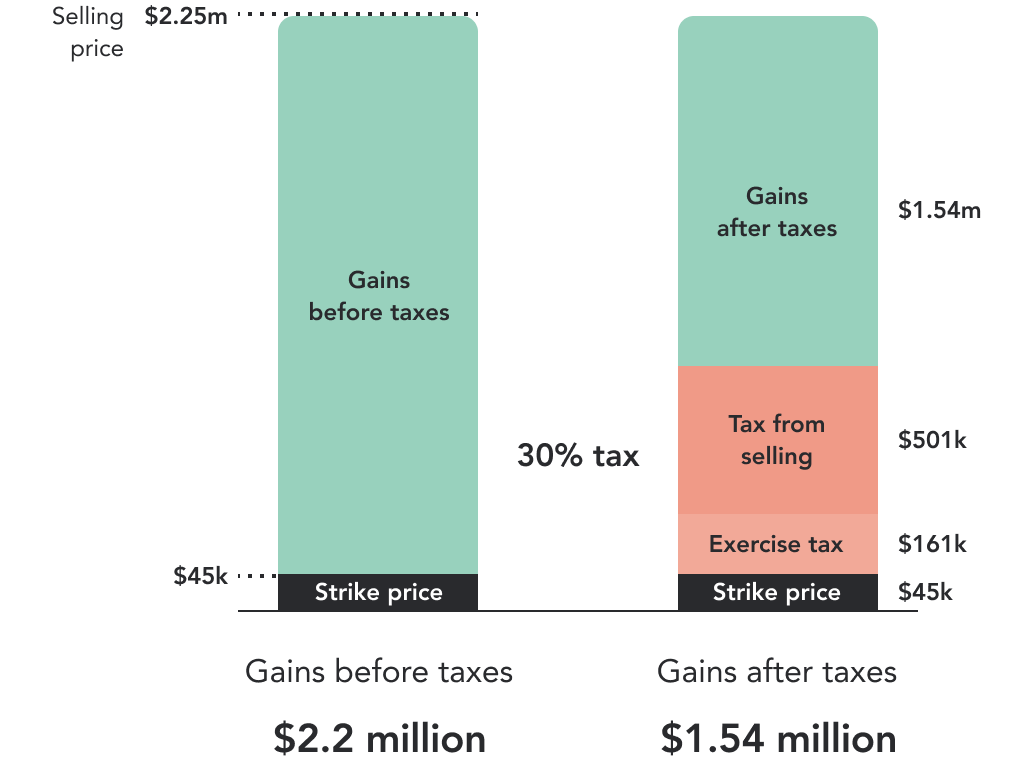

But you get a major tax discount if you exercise them at least 12 months before selling (and you don’t sell them within 24 months after grant).

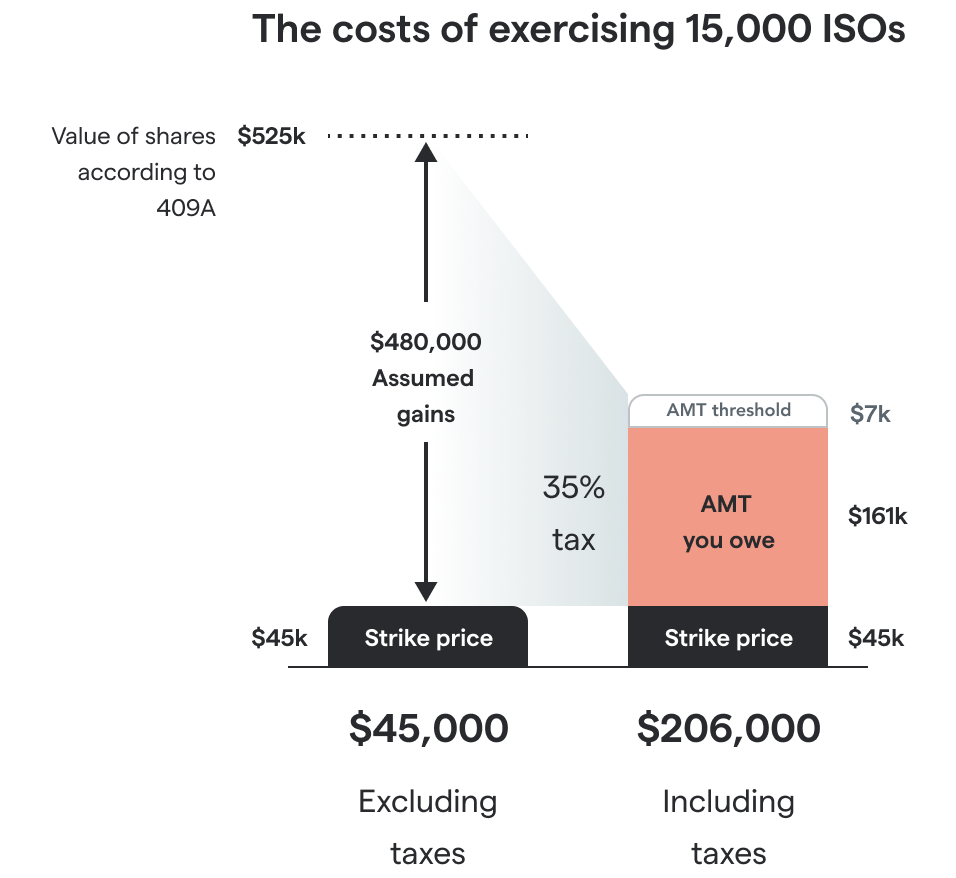

The problem? You already need to prepay a part of the taxes the moment you exercise.

If you can’t afford that, then you can't exercise and you miss out on the overall tax discount.

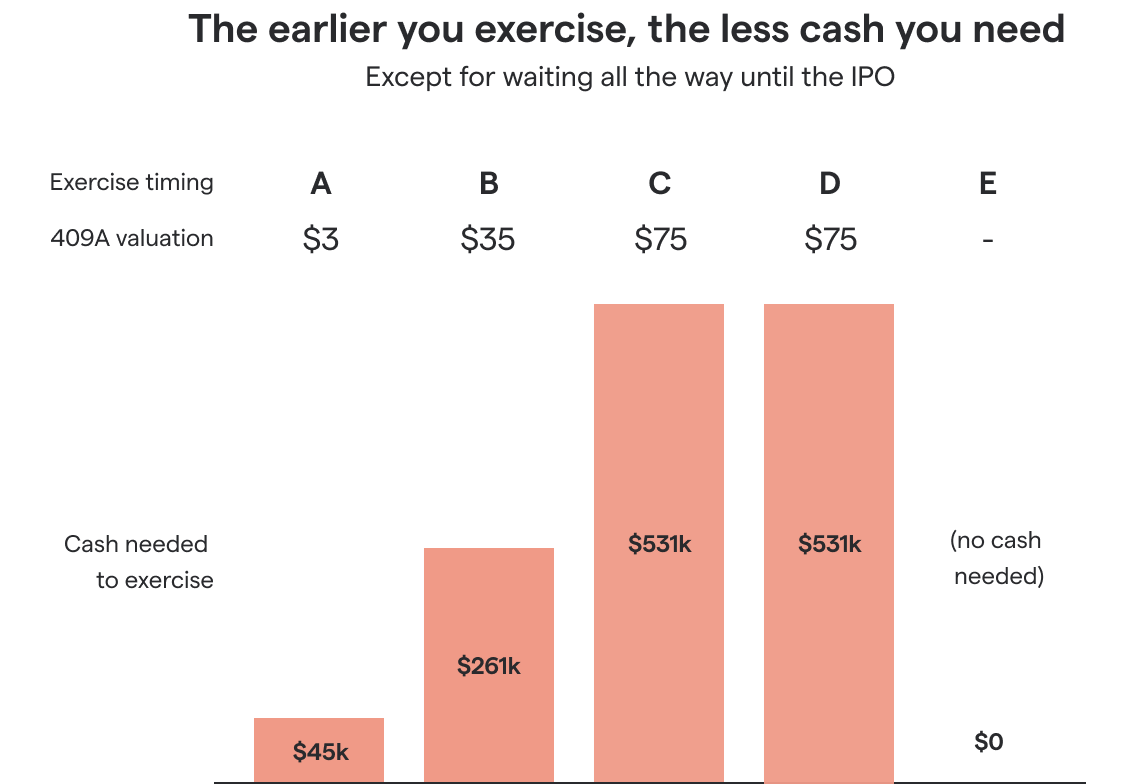

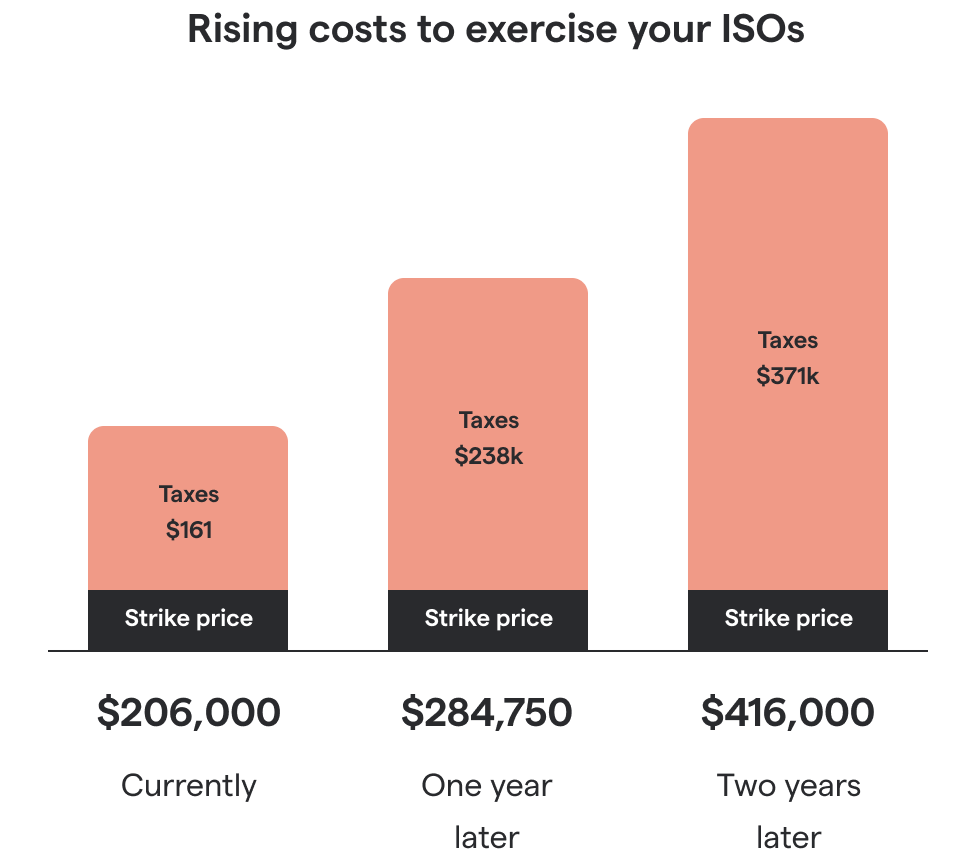

What makes it extra tricky is that the later you exercise, the more tax you'll need to prepay – assuming your company is growing (and its 409A valuation keeps rising).

So...

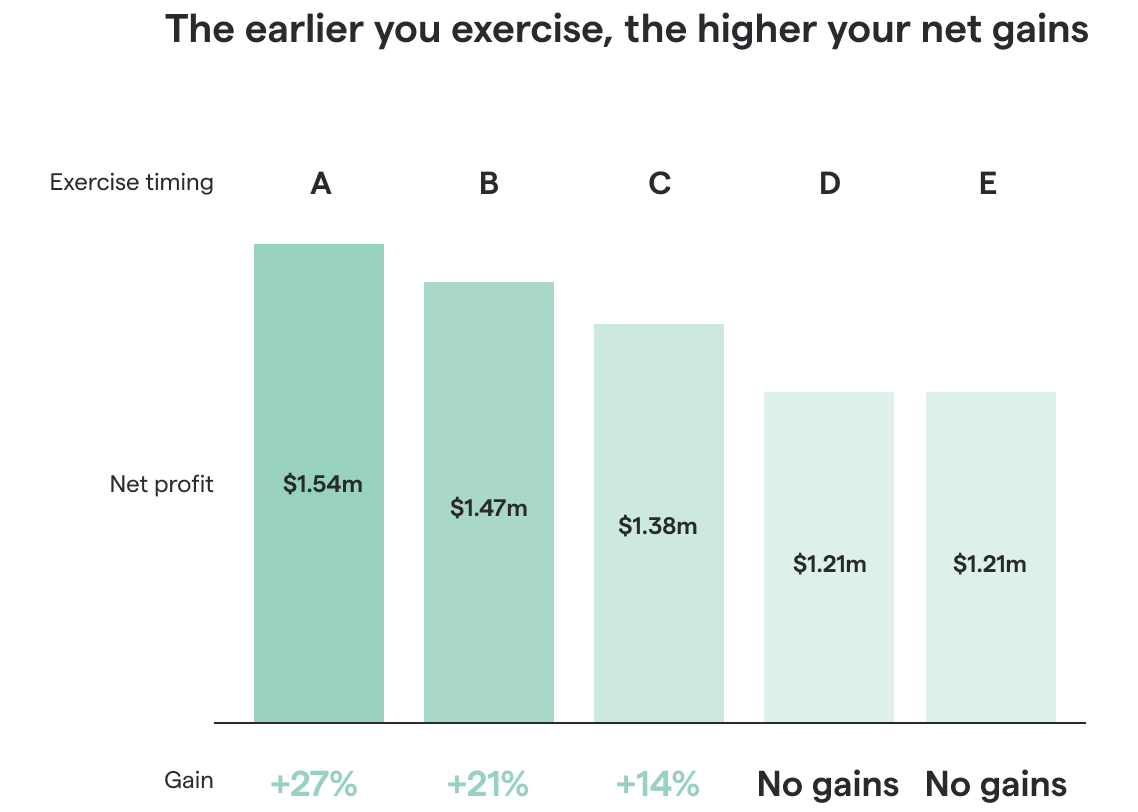

To get the most out of your ISOs when your company IPOs, exercise them at least 12 months before you sell them. And the earlier you exercise, the less cash you need to do so (assuming your company is growing).

Warning: when you exercise, your employer won't withhold the taxes you owe. It’s up to you to pay them.

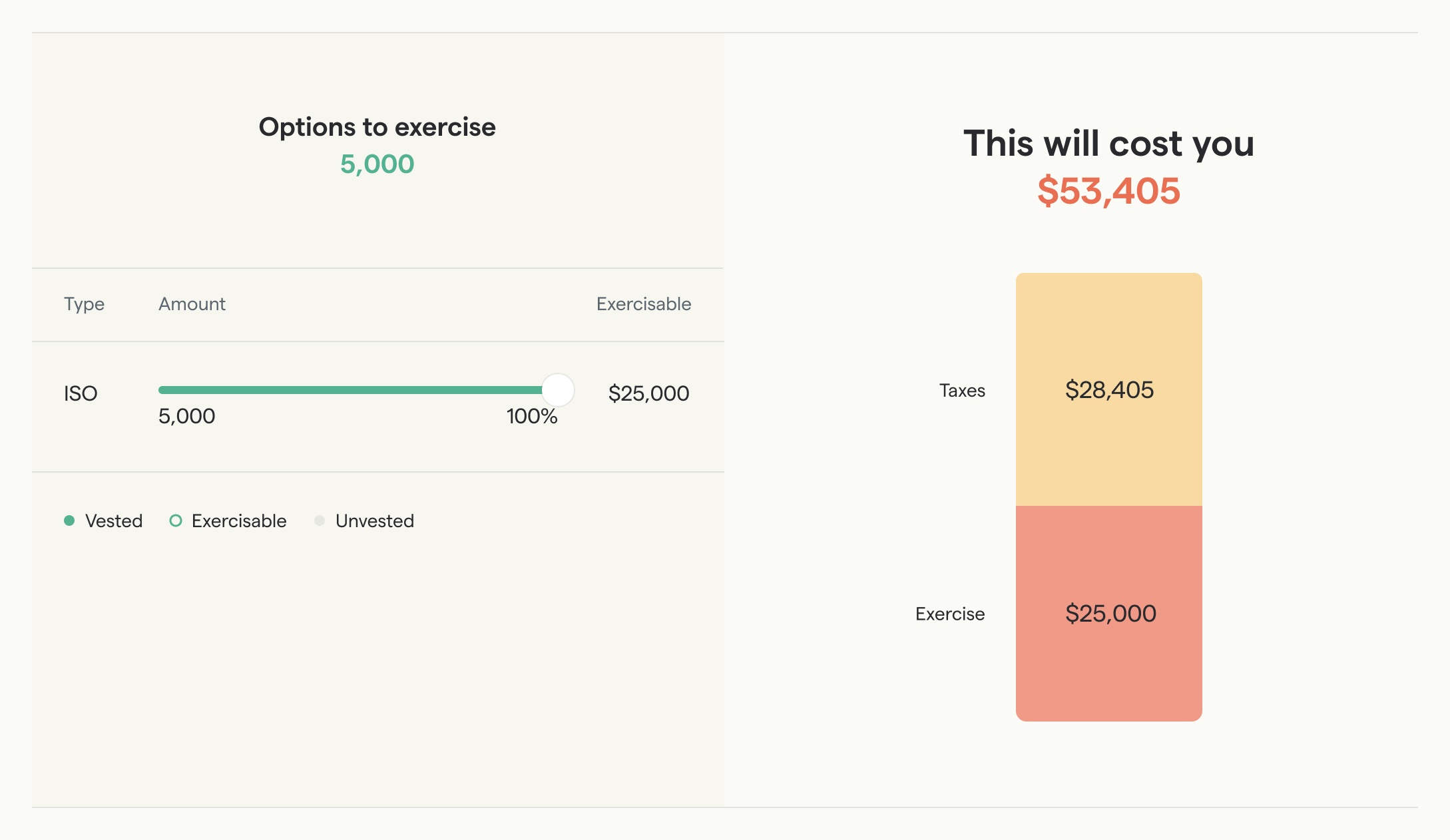

(Want to know exactly how much you'll be taxed? Use our free Stock Option Tax Calculator for taxes on exercise and the Stock Option Exit Calculator for taxes on sale.)

What are ISO stock options?

Incentive stock options (or ISOs) are a type of stock option that gets a more favorable tax treatment than other types of stock options. When early-stage tech startups give you equity compensation, it’s usually in the form of ISOs.

Incentive stock options vs non-qualified stock options

With ISOs, you’re less likely to be taxed when you exercise them than with NSOs. And if you are taxed, it’s at a lower rate.

Then later, when you make money with them, you’re taxed again at an effective rate that’s often lower than with NSOs (more on that later).

ISOs can only be given to employees, and are specifically meant as a form of employee compensation. Startups can award NSOs more broadly, for instance to external advisors.

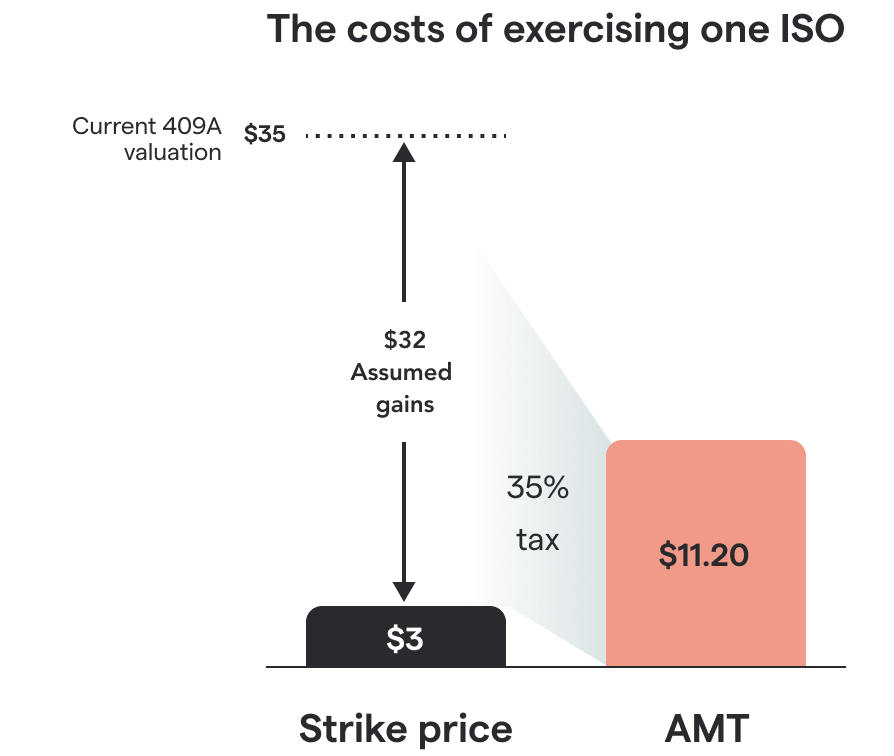

Finally, exercising ISOs are taxed under the alternative minimum tax system rather than the regular tax system. This makes it much more complicated to fully understand, but it does create the opportunity for some advanced tax optimizations.

The big picture: what’s the best tax strategy for your ISOs?

Before the rest of this guide dives into the details, let’s take a holistic look.

If you work for a constantly growing startup that ends up succeeding, the best tax strategy could be to exercise your ISOs as early as possible.

That’s because:

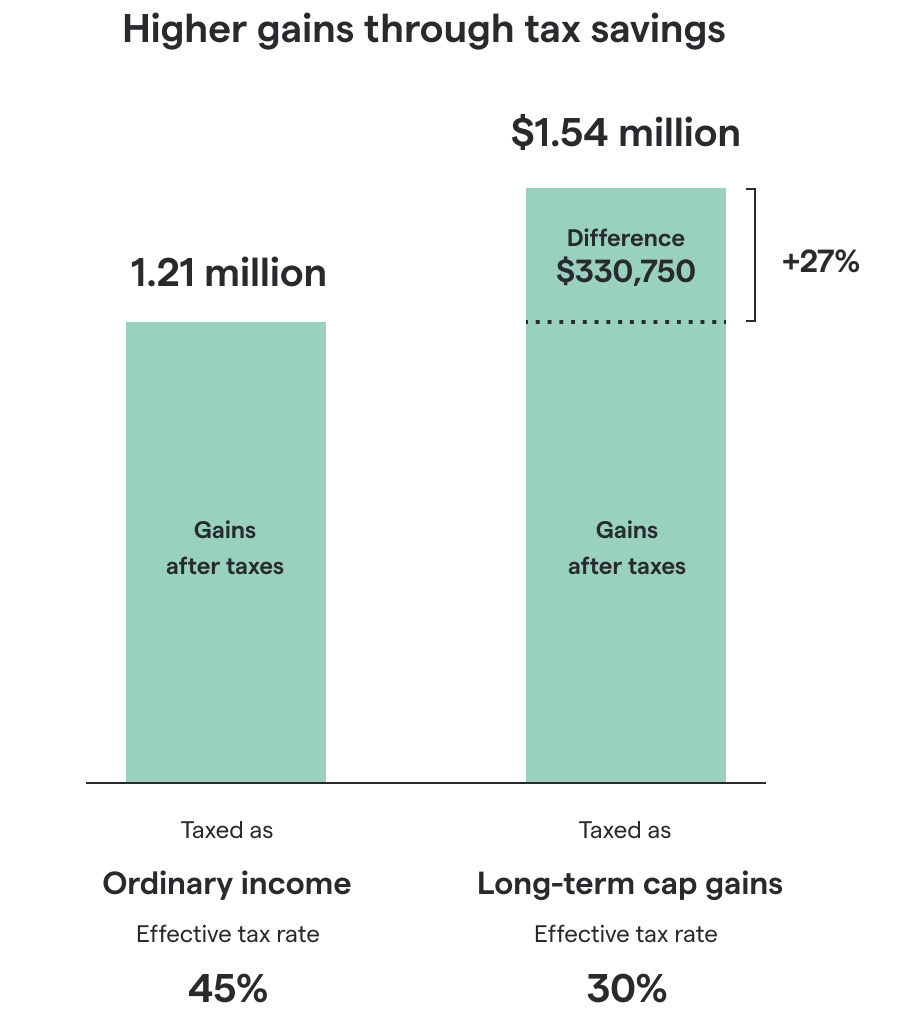

- You may net up to 27 percent more through long-term capital gains tax savings

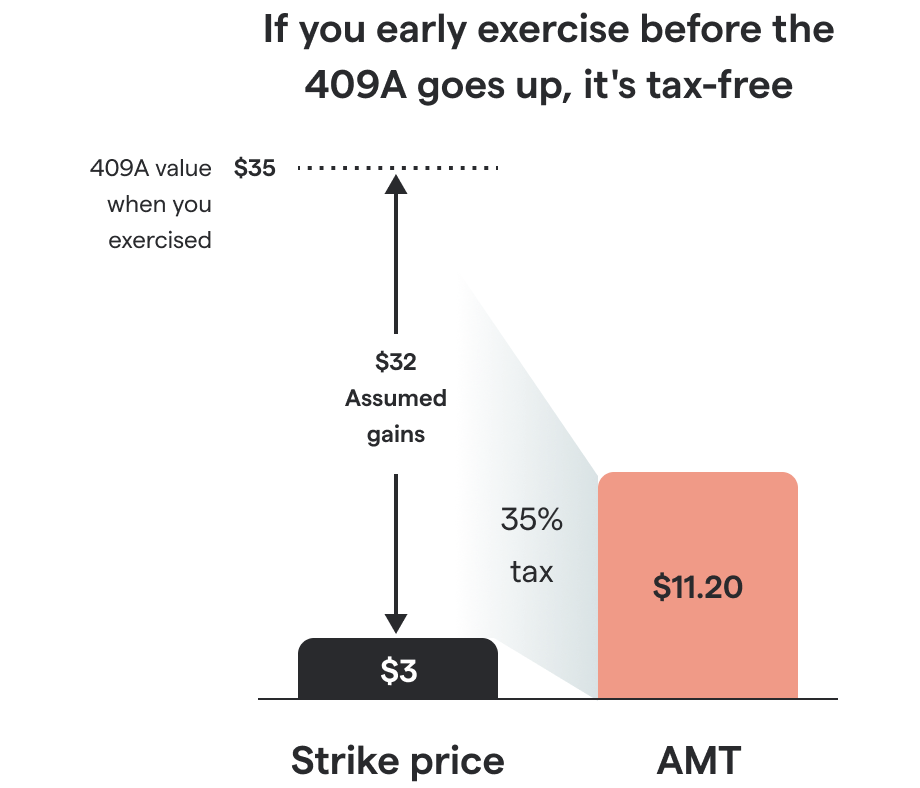

- The earlier you exercise, the less upfront cash you need to exercise

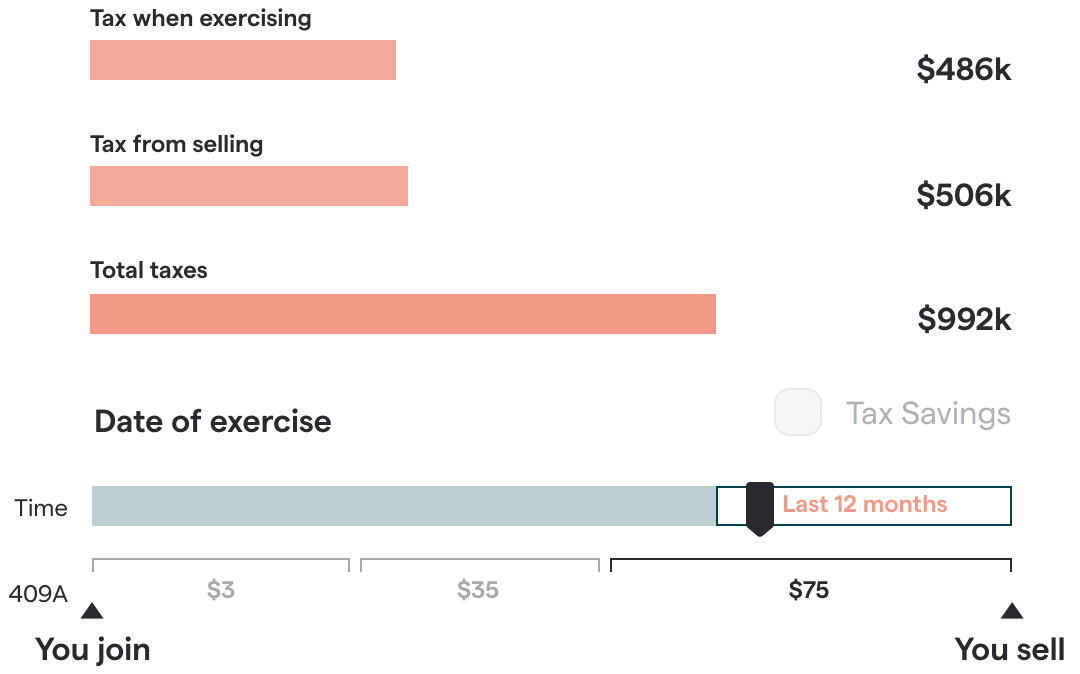

Here’s a real-world example:

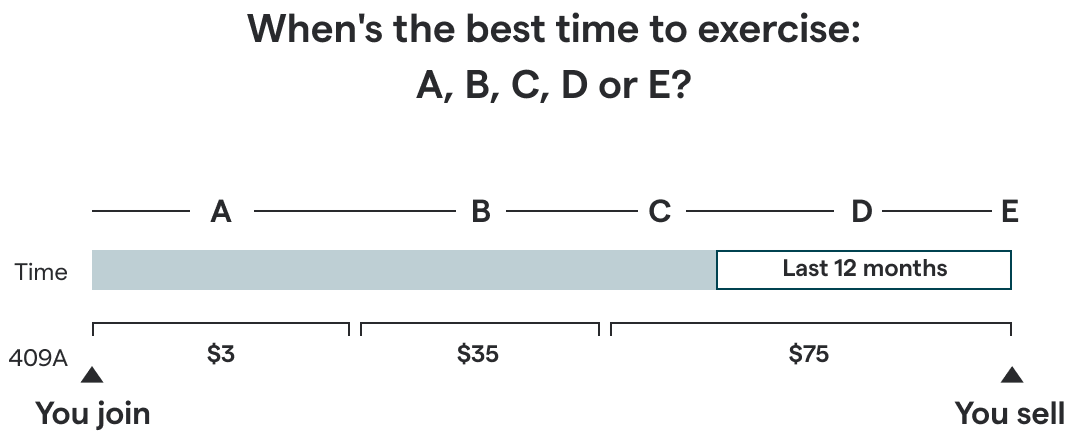

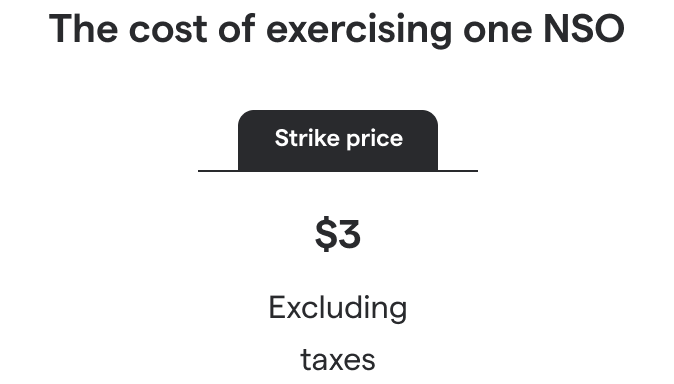

Say you join a startup and get 15,000 NSOs with a $3 strike price. Eventually, the company IPOs and you get to sell the shares for $150 each.

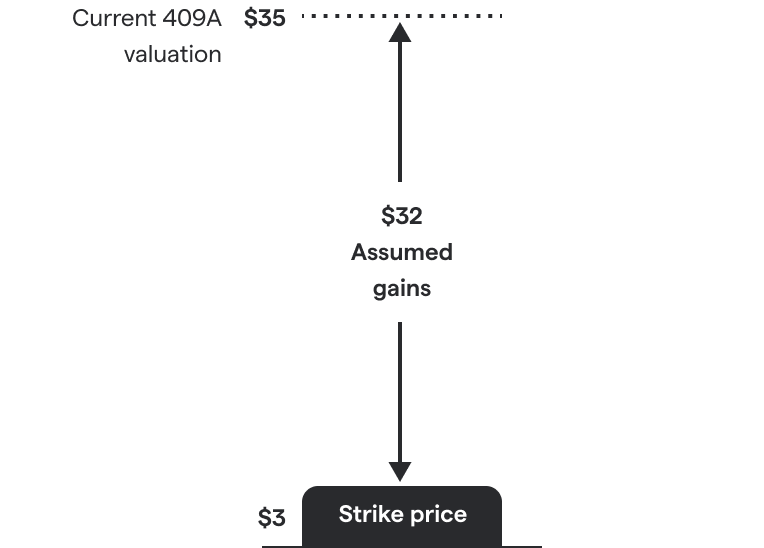

Over time, the 409A valuation (also known as fair market value) of your company grows.

Say this is the timeline:

- Year 1: You join the company when the 409A valuation is $3

- Year 2: 409A grows to $35

- Year 3: 409A grows to $75

- Year 4: The company IPOs, and you sell your shares for $150