In conclusion:

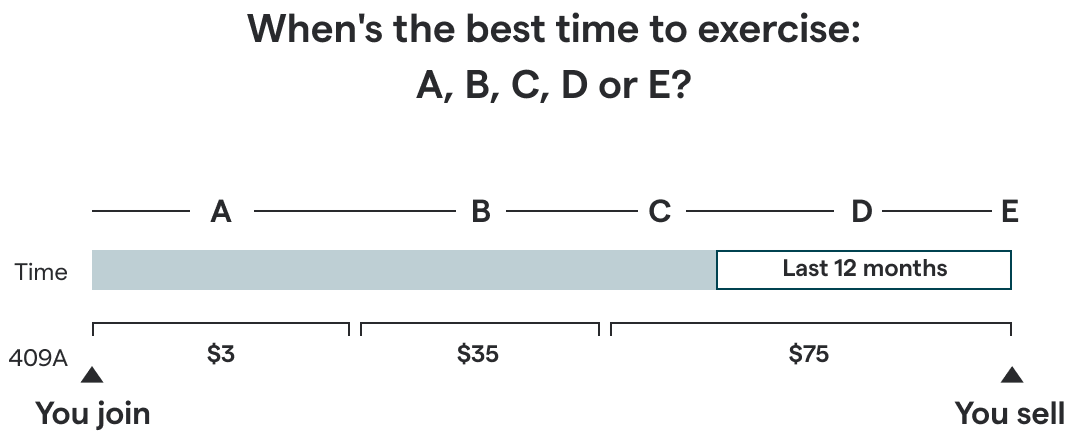

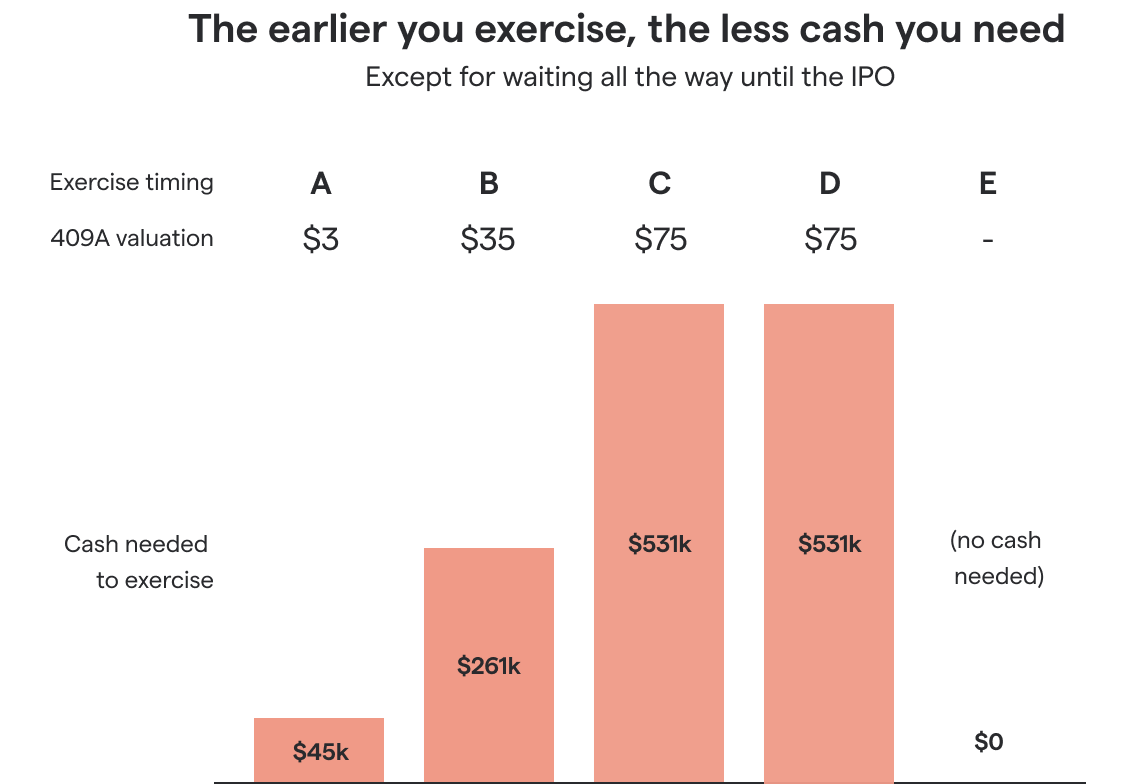

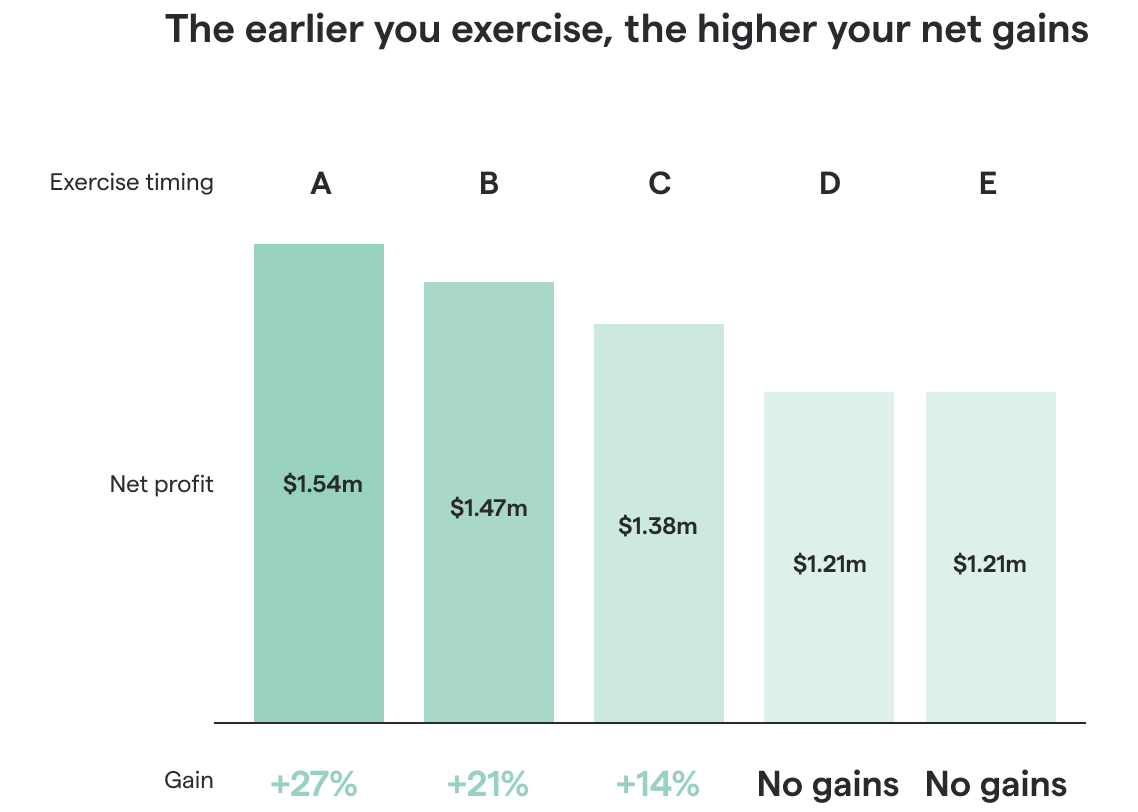

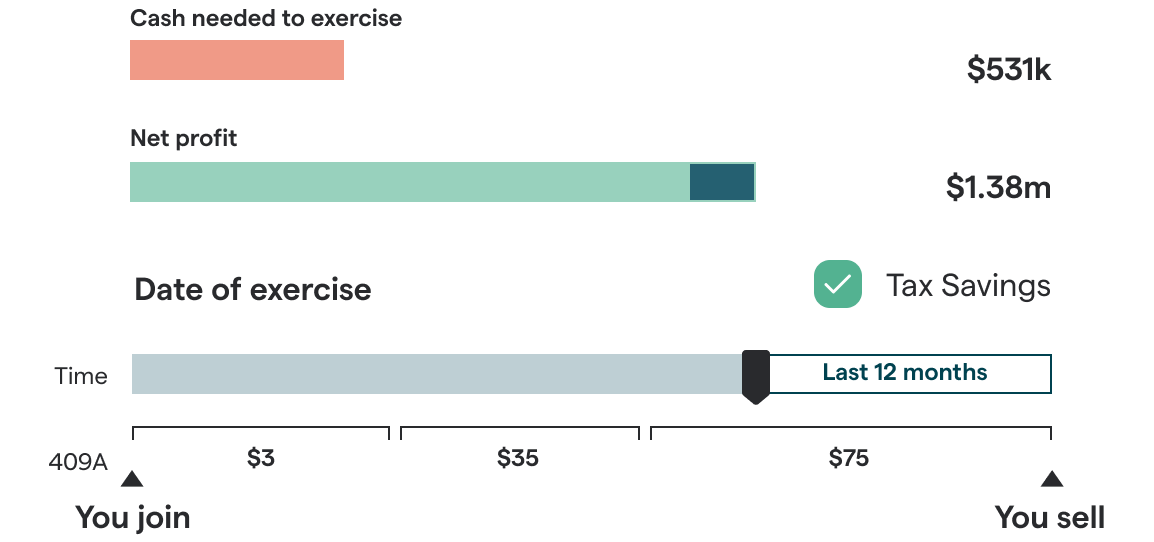

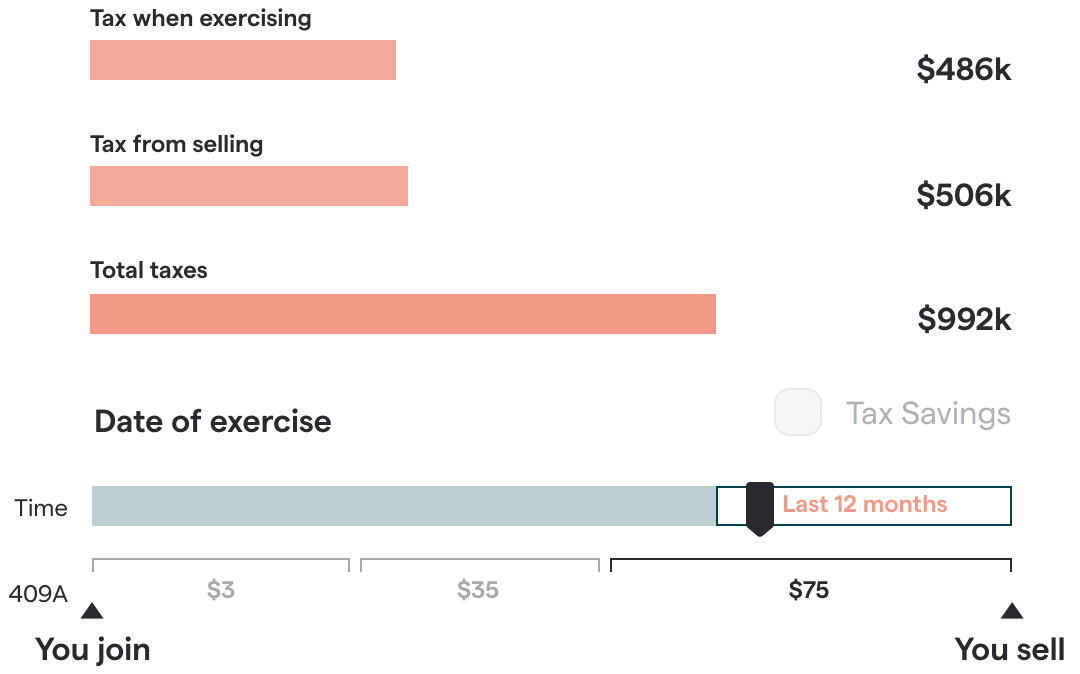

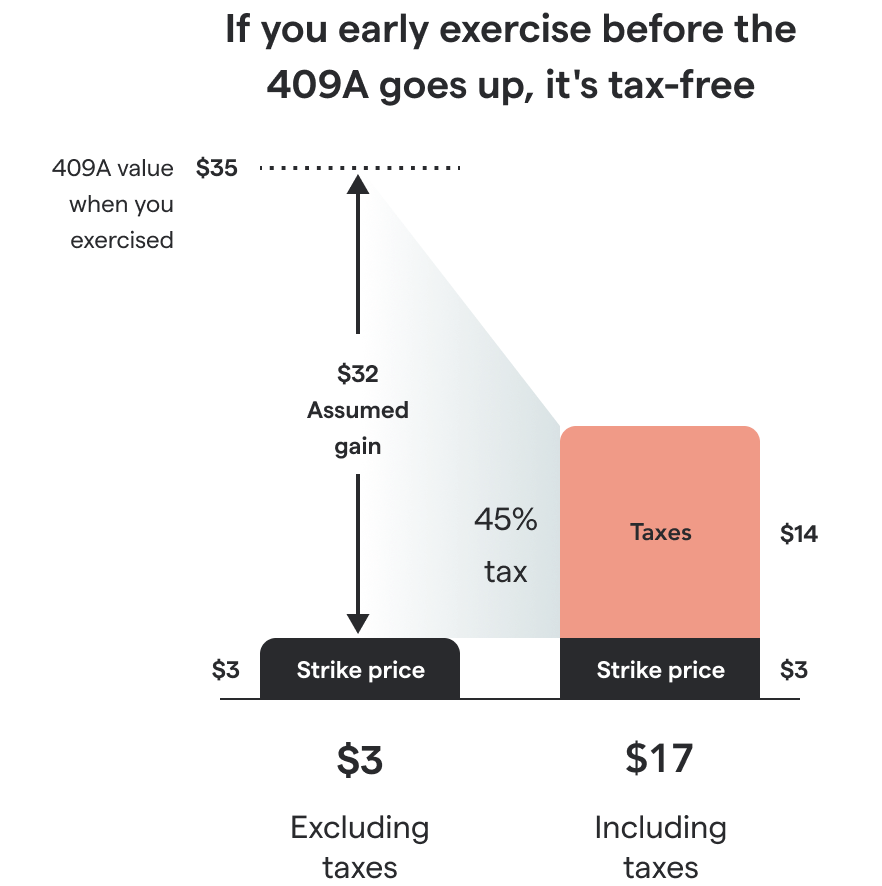

If you work for a constantly growing startup, then the longer you wait to exercise your NSOs, the less net gain you’ll end up with and the more cash you’ll need to do it.

What exactly is a 409A valuation?

The 409A valuation (a.k.a. fair market value) is an appraisal of the value of a company share for tax purposes. Your employer is required to have it re-assessed by a third party at least once a year – or when something impactful happens, like a new funding round.

The 409A reflects company growth. Is the company in a better place than last time? Then the 409A will rise. So a higher 409A is a good sign for the company, but it’s bad for your tax situation if you haven’t yet exercised.

More on 409A valuations here.

What if exercising my NSOs is too expensive?

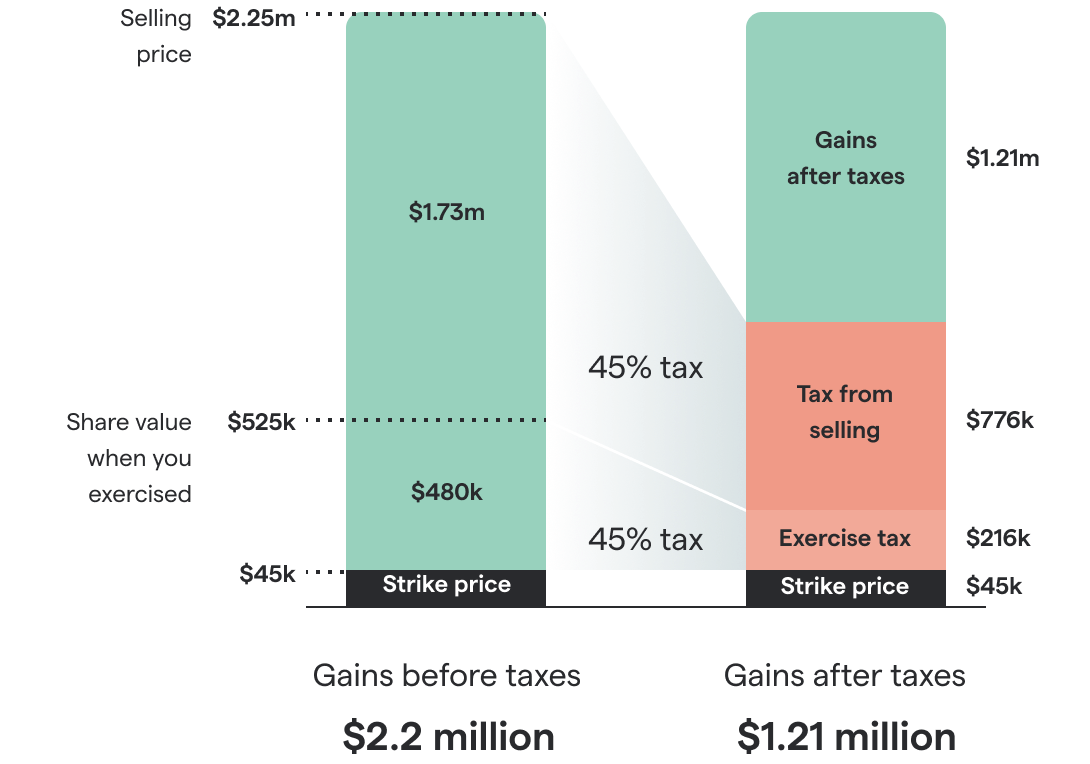

Of course, $261k or even $531k is a huge amount to pay for your NSOs.

Unfortunately, these aren’t uncommon numbers for employees at the most successful and high-growth startups.

See, for example, how much these Snowflake and DoorDash employees had to pay. Among Secfi users, the average exercise cost is $505,923.

Even if you have that kind of money, putting your personal savings on the line is risky since it’s not guaranteed that your company will actually manage to reach a successful exit

So what do you do if you still want that tax savings? Or what if you recently left your company and now have a deadline to exercise your NSOs?

That’s exactly why exercise financing exists, which we offer at Secfi.

Here’s how our exercise financing works:

- We cover your exercise costs (including taxes)

- You pay us back after your company exits

- It’s non-recourse, meaning you don't risk your personal assets – if the exit never happens, you won’t have to pay us back

- You stay the owner of your shares – you’re not selling them to us or anything like that

We make money only if there is a successful exit. If there is, you’ll pay us back more than the original amount. (But because of the tax savings, you’re often still at a net benefit vs not having exercised.)

If there’s no exit, you don’t owe us anything (and we’ll take the hit).

See if exercise financing is available for you, and at what rates.

Is it always better to exercise my NSOs as early as possible?

No. In the example, we made two assumptions:

1. Your company successfully exits (i.e. you get to sell your NSOs at a gain)

2. The 409A valuation of your company keeps rising

Regarding #1, most startups never get to that point.

That’s why exercising early on is risky. If the company later goes out of business, you’ve lost the money you spent.

If you want to exercise your NSOs but don’t want to risk losing money, financing could be a solution.

Regarding #2, sometimes the 409A valuation of a company temporarily dips. This means you can exercise at a lower cost, so in that scenario waiting actually makes it cheaper.

It’s difficult to time this, however. If you are long-term optimistic about the company, you should expect the 409A valuation to go up – unless you foresee a specific reason why the company would take a hit in the short term.

Now that you’ve got the big picture, let’s dig into the details of just how NSOs are taxed...

So how exactly are NSOs taxed?

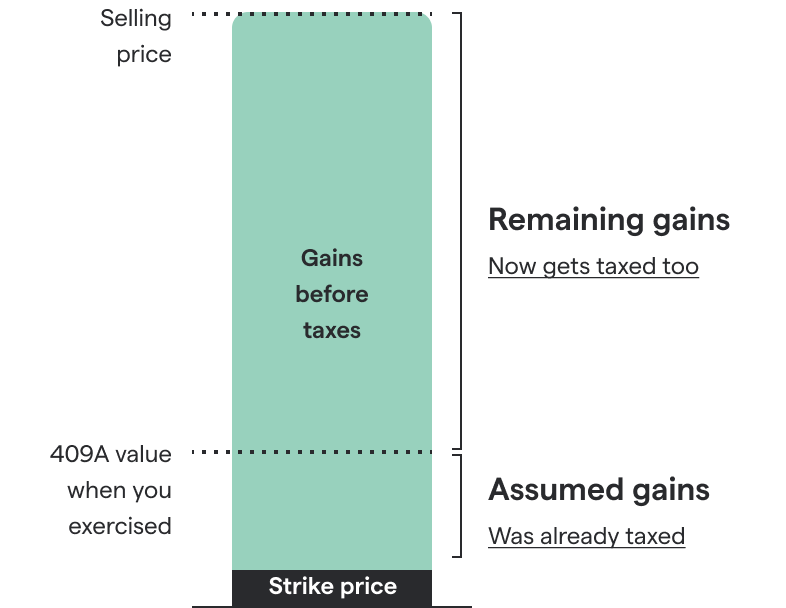

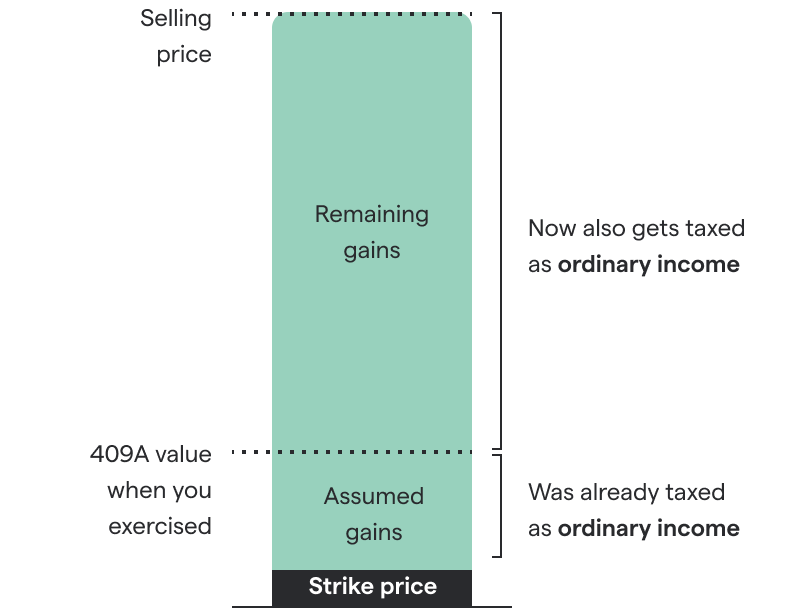

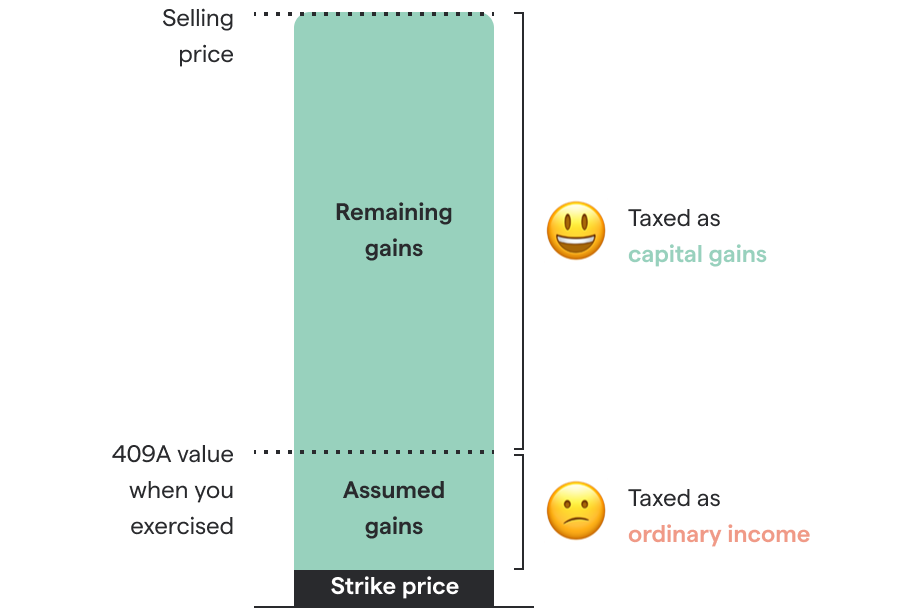

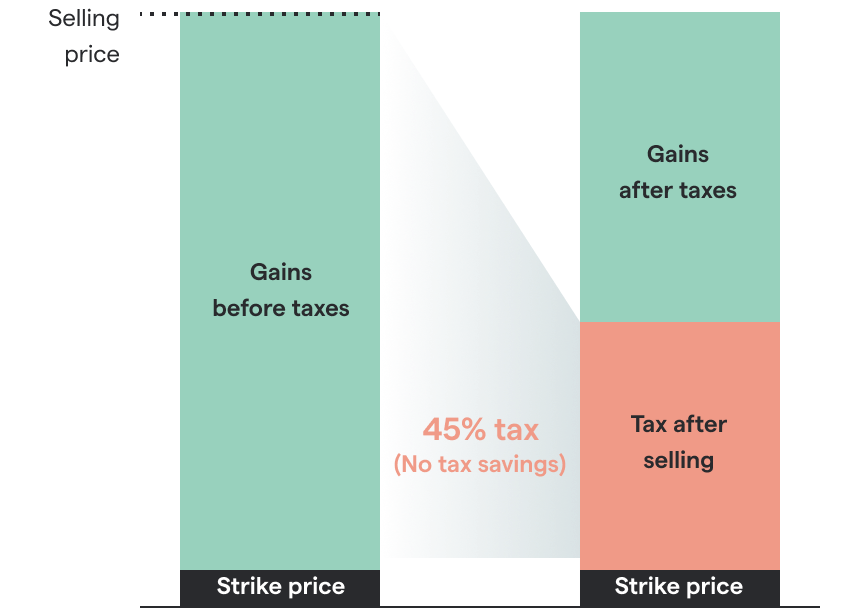

NSOs are taxed at ordinary income tax rates (the highest possible rate, just like your salary) twice:

- When you exercise them

- Then again when you make money with them after your company exits.

But as we already mentioned, usually the earlier you exercise, the less you’ll owe (especially for fast-growing companies).

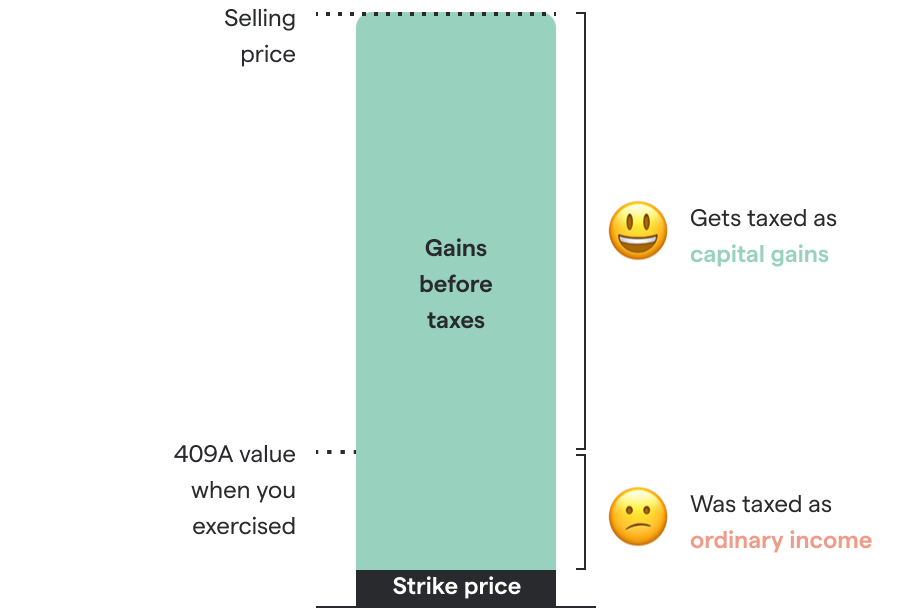

That’s because some of your taxes convert from ordinary income rates to the lower long-term capital gains rates. More details on how this works are below.

Are NSOs taxed when initially granted?

No. There’s no tax due when your company initially grants you the NSOs (i.e. awards you with them).

Are NSOs taxed when they vest?

No. After the initial grant, most NSOs follow a vesting schedule that dictates when you actually ‘get’ them. But when they vest, there’s still no tax due.

How are NSOs taxed when exercised?

In short:

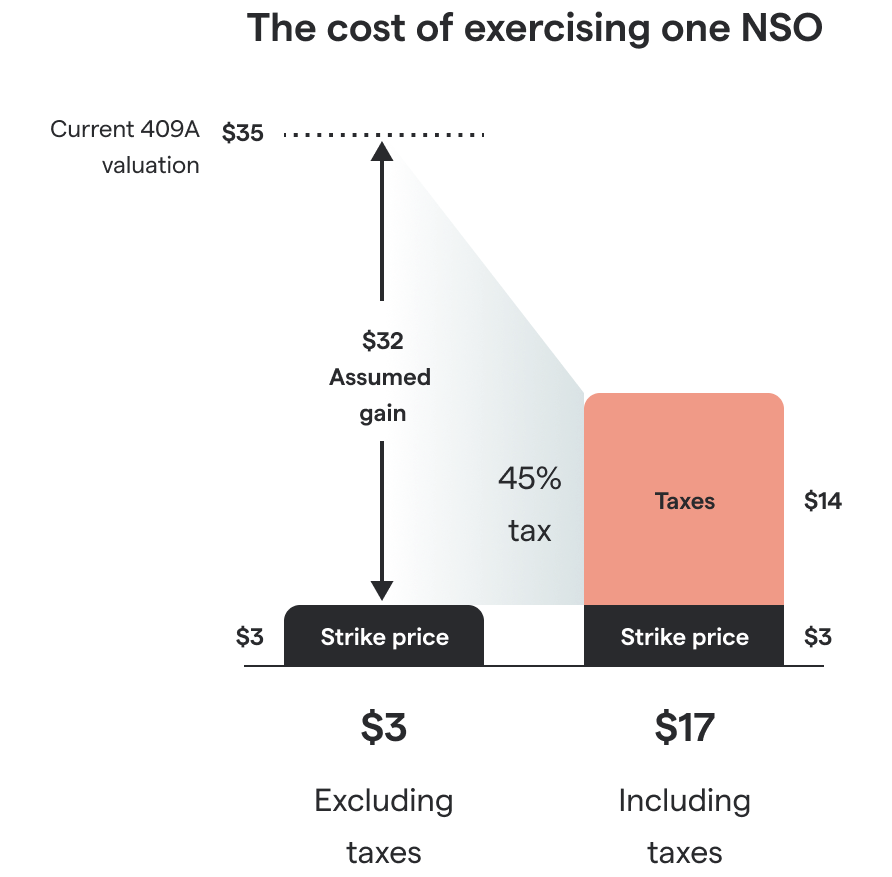

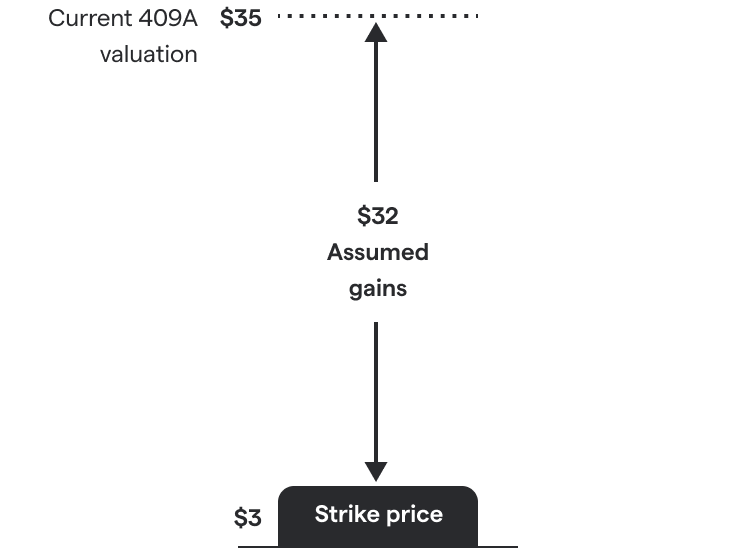

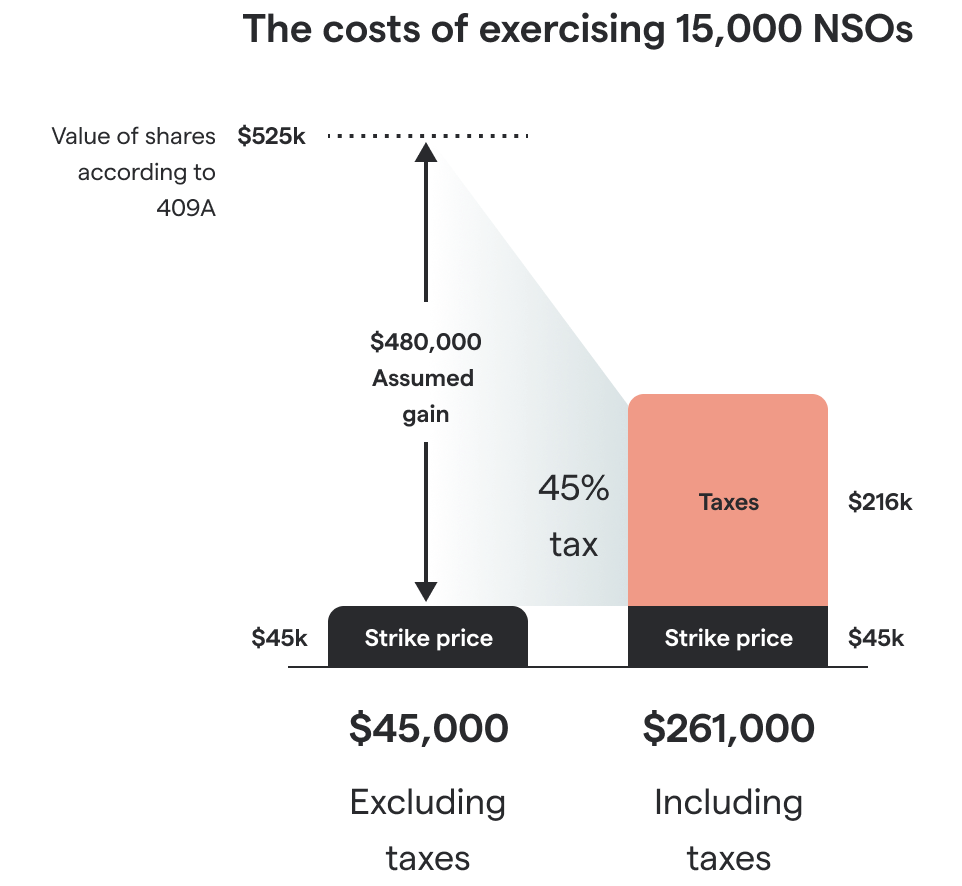

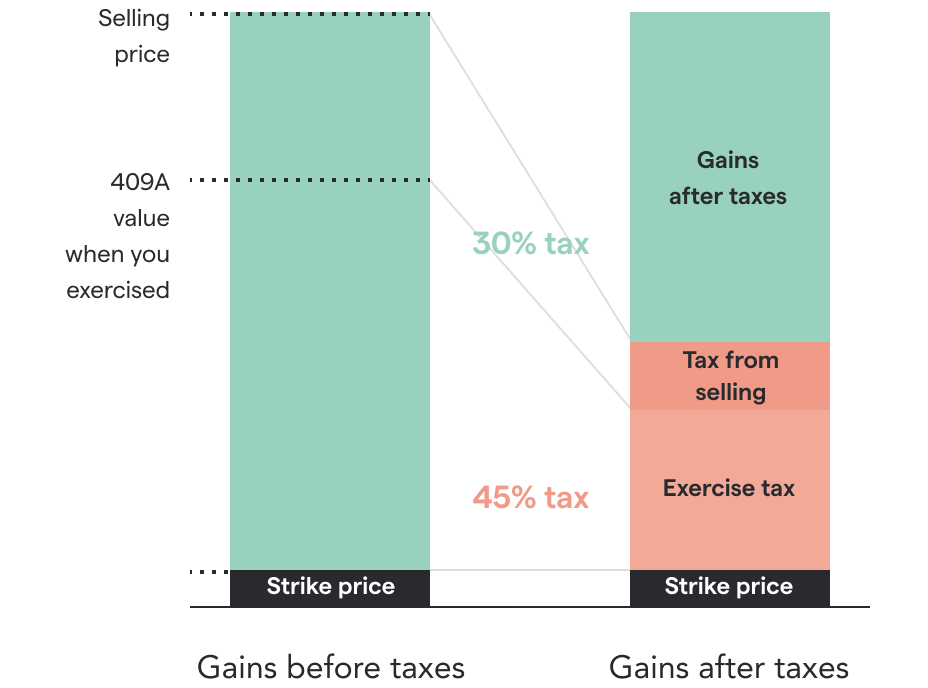

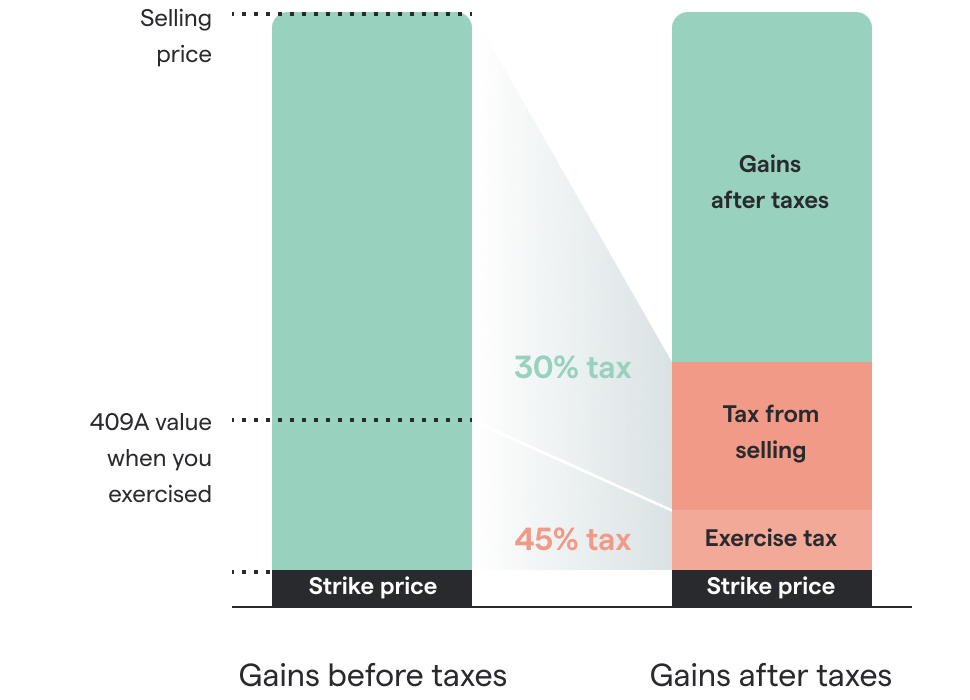

- You pay ordinary income tax rates on the difference between the strike price and the 409A valuation

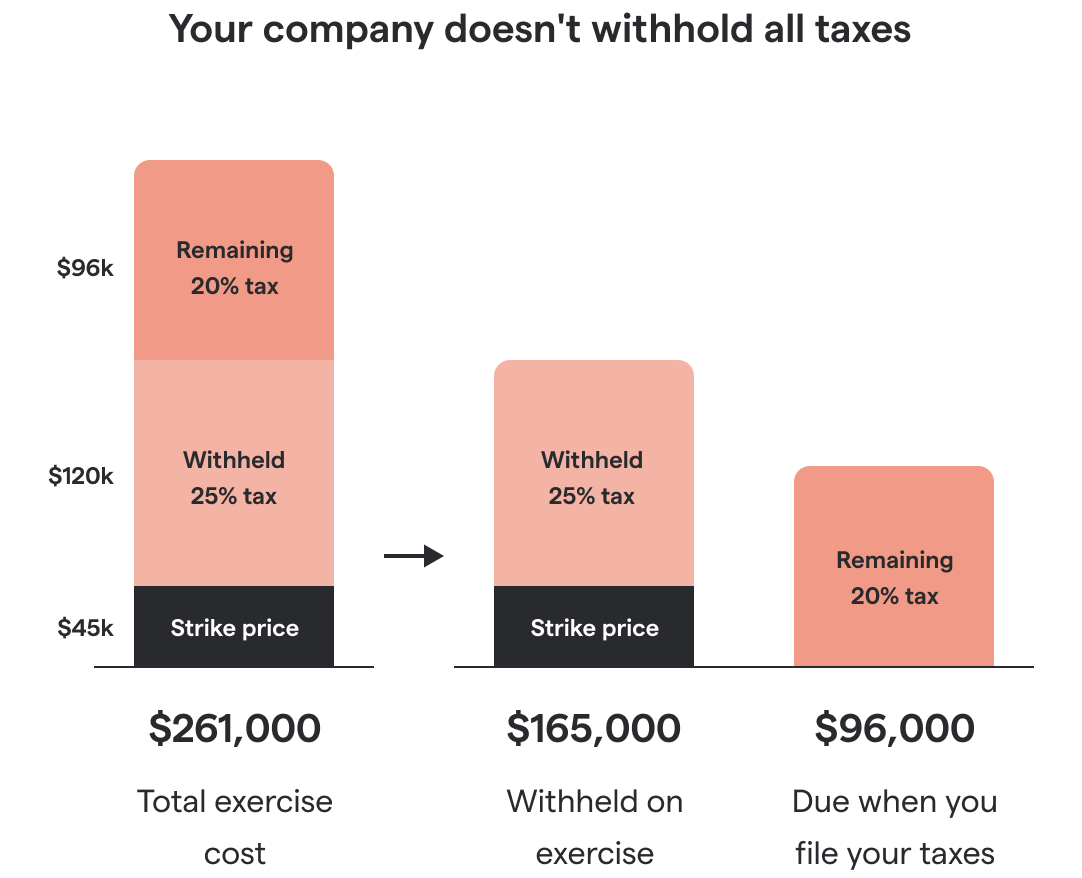

- Your employer already withholds a part, but it’s the bare minimum (usually 25%)

- You have to pay the rest to the IRS yourself

- That last part often comes as a surprise, so watch out

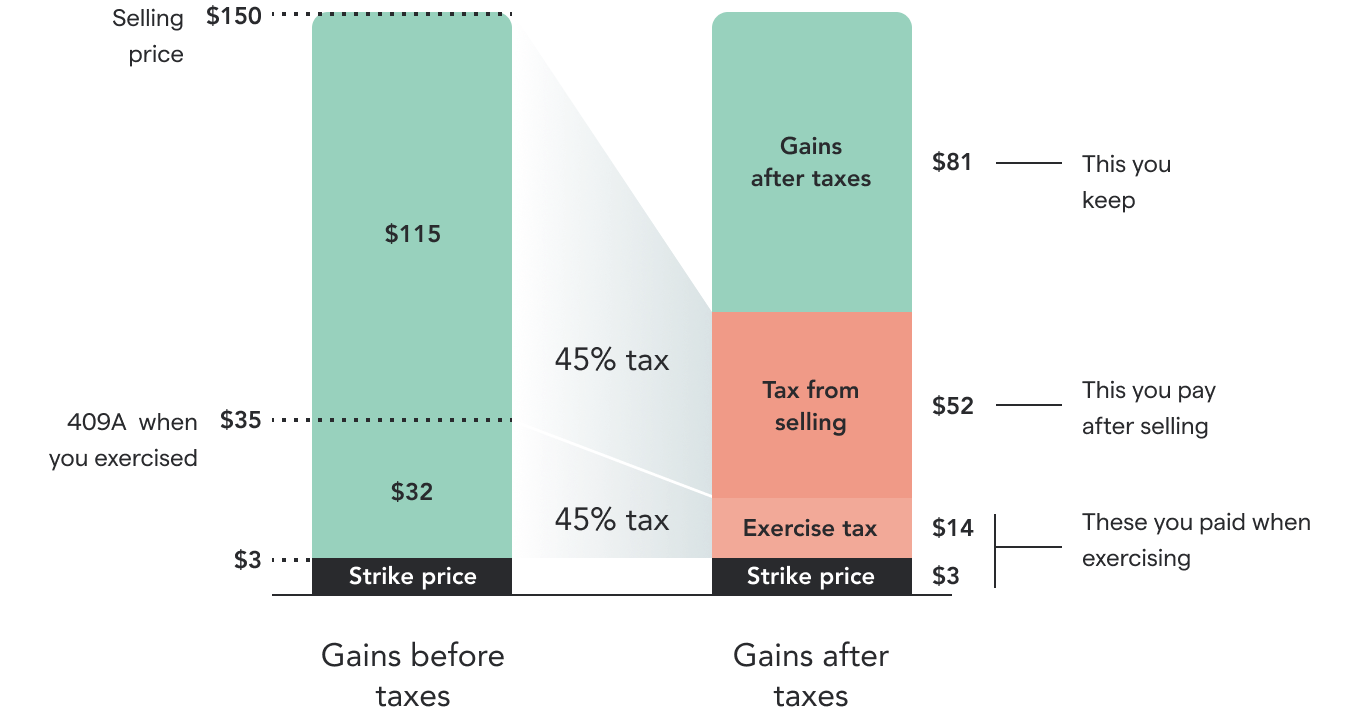

Ordinary income tax rates are usually ~35-52% for our clients in California. We’ll assume 45% in this article – use our Stock Option Tax Calculator to get a personalized figure.

The costs of exercising an NSO, visualized: