💰 Cash rules: What’s happening in banking and why?

“Cash rules everything around me. C.R.E.A.M.! Get the money, dollar, dollar bill, y’all.”

-Wu-Tang Clan

I’m back with another Founders + Funders special edition in the ongoing, hair-on-fire banking crisis.

The latest big news is the purchase of Credit Suisse by UBS over the weekend.

What’s in the deal:

- UBS is buying Credit Suisse for $3.2 billion (about 60% less than the bank was worth when markets closed on Friday).

- The Swiss National Bank will guarantee the deal by granting access to facilities that provide substantial additional liquidity, lending to UBS up to $108 billion (100 billion Swiss francs).

- The deal will not need the approval of shareholders because they obtained pre-agreement from FINMA, Swiss National Bank, Swiss Federal Department of Finance and other core regulators on the timely approval of the transaction.

In times like these, I like to go back to first principles to get to the root of the issue. Apologies if this is pedantic, but after seeing so many breathless takes on social media, it’s clear that many people have forgotten, or have never understood, how banks work.

🏦 How do banks make money?

Banks like Credit Suisse are far more diverse and complex than your local lender. They have several lines of business that operate somewhat independently. Still, the bread and butter of banking and the epicenter of the current crisis is plain vanilla lending.

Banks borrow from depositors and lend to borrowers. They pay less interest on the deposits than they earn on the loans they make. Their revenue is the difference between the interest they pay and the interest they earn.

Credit Suisse does this in Switzerland with their local banking franchise, as well as around the globe to corporate customers and wealthy individuals. Banks like Credit Suisse also earn fees for advisory services, asset management, and trading securities.

😬 So where is all the stress coming from?

In this crisis, it’s from interest rates. Banks’ business models means that they are necessarily leveraged. They borrow the money people like you deposit and then use that money to make loans. This practice of short term borrowing — which is normal, meaning you can get your money out anytime — and long term lending is called “maturity transformation.” Plus, this crisis is different from the GFC which was a credit crisis.

Bank liabilities are mostly short-term and their assets are mostly long-term (or longer term than their liabilities). When interest rates rise, the value of fixed interest rate loans/bonds goes down.

🤔And why is that?

A bond or a loan’s value (bonds are effectively loans) is driven by the interest rate it pays, the risk that the borrower will default, and the expected recovery in the case of that default.

When investors think about the price they’re willing to pay for a bond or loan, they compare it to all other investment opportunities. So, bonds and loans with similar characteristics (interest rates, risk of default, etc.) have similar prices. When interest rates in the economy change, the opportunities for investors also change. Therefore, the price investors are willing to pay for bonds and loans changes too.

Consider this example: If you buy a default risk-free government bond that pays 5% interest for five years and then, the next day, interest rates go up to 6%, why would anyone pay full price for your bond that only pays 5%? They wouldn’t, they’ll pay you something less. If you paid $100 for your bond that matures in five years but now people can pay $100 and get a bond that pays 6% a year and matures in five years, they’ll pay you $97.44. Because that’s the amount that makes the yield-to-maturity (or total return) on the two bonds equivalent.

Bank deposits are fixed and the market value of the loans they make is variable and dependent on interest rates. As interest rates have risen, the value of the loans on bank balance sheets has declined.

This isn’t a secret. Investors and regulators know that the marketable value of the loans on bank balance sheets have declined. They know what interest rates have done. So why are we suddenly in the grips of a crisis? Panic.

“How did you go bankrupt?"

Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

-Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

Despite the fact that none of this stuff has been a secret, all of a sudden, depositors started to run. Once a bank run starts, it’s hard to stop. Think about this scenario.

Imagine that a bank has taken in $10 million in deposits and has lent out all $10 million in hopes of making a nice profit on all the interest they receive from the loans. All is going well and the bank is collecting interest as it’s due, until one day, a borrower decides to withdraw $2 million. What does the bank have to do? They have to sell their assets to raise the cash to pay the $2 million. If interest rates have risen, and they can only get $1.5 million today for a loan they made in the past, they will realize a loss of $500K and have to sell even more loans to get the $2 million they need to meet the depositor withdrawal.

If you are a depositor, what do you do in this situation? You rush to the bank and demand your deposit back as soon as you can. So do all the other depositors. The longer you wait the less likely you are to get any money back! This phenomenon is called a “run on the bank.” The bank will collapse and people will lose money which will harm the economy and may cause other borrowers to be unable to repay their loans which may cause more runs and a vicious feedback loop may start.

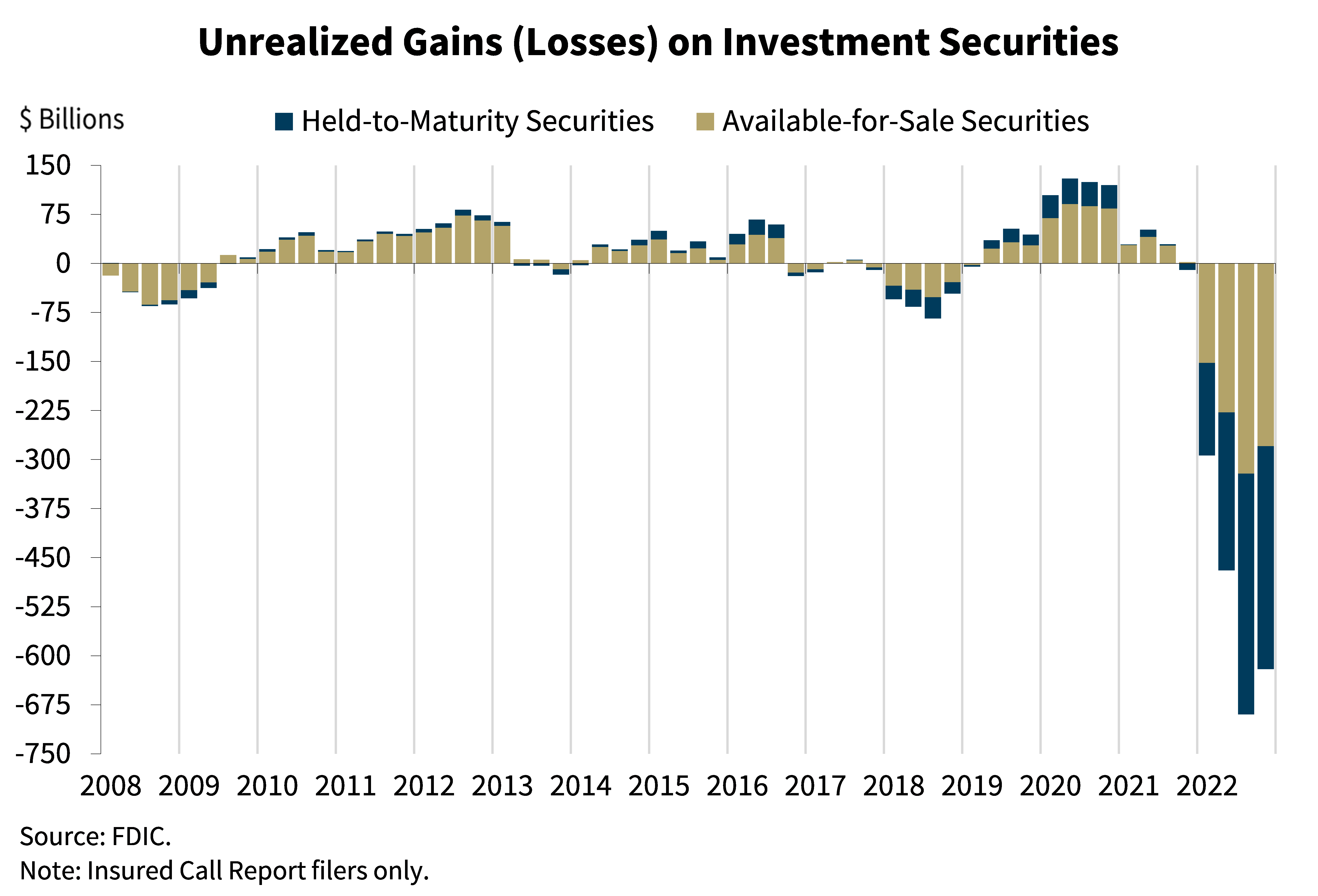

The graphic below has gone viral. It shows the unrealized losses on loans sitting on bank balance sheets.

This looks scary, but it only matters IF THERE’S A RUN ON THE BANKS. The loans banks have made in the past are contractual and mostly high quality (much higher quality than they were in 2008). The money will be paid back, it’ll just take time.

Bank earnings will be low because the rates on the long-term loans are low, but that’s not existential. The way banks fail is if there’s a run on the bank and banks are forced to sell their loans in a fire sale

Imagine all the furniture and fixtures in your house. Their total value probably represents some real money. However, if you had to sell all of it today because you absolutely needed the cash, how much do you think you could get? Not much is the answer. This is what’s happening with the banks. Because depositors are fleeing, they are selling assets at a loss. The more panic, the worse the prices, and the worse the crisis gets.

🙍 So…how does it stop?

Confidence in the system needs to be restored. People need to feel that their deposits are safe, so they leave them in the banks, so the banks don’t have to sell their assets at a loss.

How do we get there? Not with declarations of financial health from the banks…nobody believes that stuff. They always say the same thing!

The only solution is government intervention. And that’s what’s been happening. The Swiss government and the Swiss National Bank arranged this marriage between UBS and Credit Suisse — simultaneously providing tons of liquidity. As part of the deal, the Swiss National Bank will lend UBS up to $108 billion (100 billion Swiss francs). The hope is that this lending facility will plug the hole left by depositors who have withdrawn their money and stem the tide of future depositors leaving.

In the US, depositors of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank were given an explicit unlimited guarantee by the FDIC, above the typical $250K per account limit. The Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) was created to allow banks to borrow from the federal reserve by pledging qualifying bonds as collateral at face value. Larger banks together, deposited $30 billion at First Republic to shore up their cash position. Additionally, central banks around the world have coordinated to provide what amounts to short-term US dollar loans to financial institutions to ensure they have the dollars when and if they need them. The hope is that these actions, and whatever comes next, will provide banks with enough liquidity that they can meet depositor withdrawal demands without selling assets in a fire sale.

In the end, all that matters is confidence in the system. No bank, no matter how well capitalized, can survive a run on its deposits. If confidence is restored, we go back to business as usual, if not, look out below.