Maximizing Your Employee Stock Options for Long-Term Gains: ISOs, NSOs, and IPO Strategies

Making the most of employee stock options

Are you wondering how to maximize your employee stock options before your company’s IPO? Whether you’re holding Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) or Non-Qualified Stock Options (NSOs), there are strategic tax planning steps you can take to reduce taxes and optimize long-term capital gains. Here’s what you need to know.

How Long-Term Capital Gains Tax Affect Your Employee Stock Options

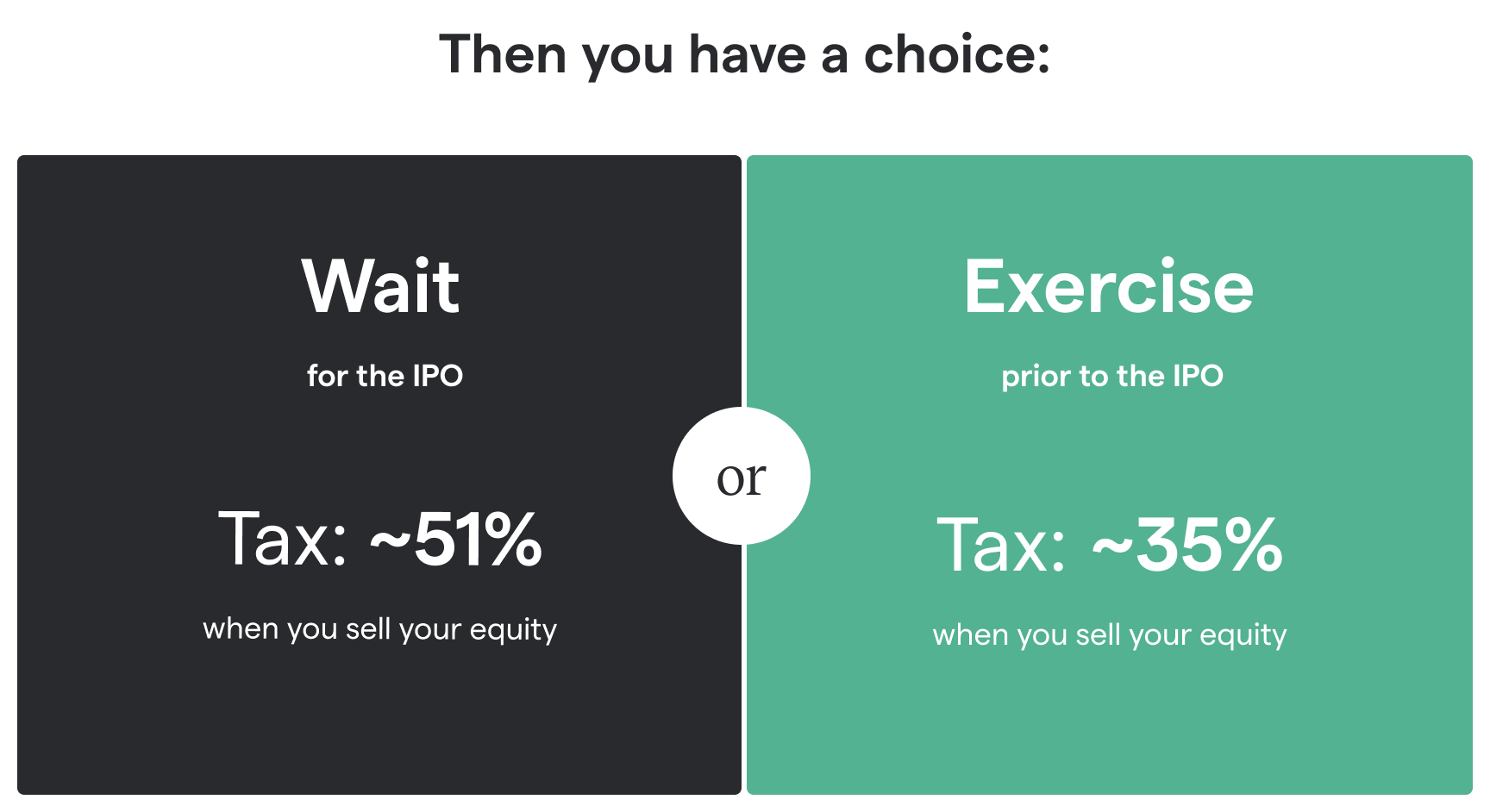

First, you have a choice:

Wait until the Initial Public Offering (IPO) to exercise your stock options and pay ~51 percent in taxes once you sell your equity...

OR

Exercise your stock options before the IPO and only pay ~35 percent in taxes.

This is due to a U.S. tax rule called long-term capital gains.

The gist: money you make selling stock you’ve owned for at least 12 months is taxed more favorably. So if you exercise now, you can have that tax savings unlocked by the time you can finally sell your shares after the IPO.

(More details on long-term capital gains further on in this article.)

Case Study: How Long-Term Capital Gains Affected Pinterest Employees’ Stock Options

Pinterest went public in 2019. After the usual 6-month lock up period, employees could sell their equity in October.

Here’s what three of them earned with- versus without exercising their pre-IPO stock options.

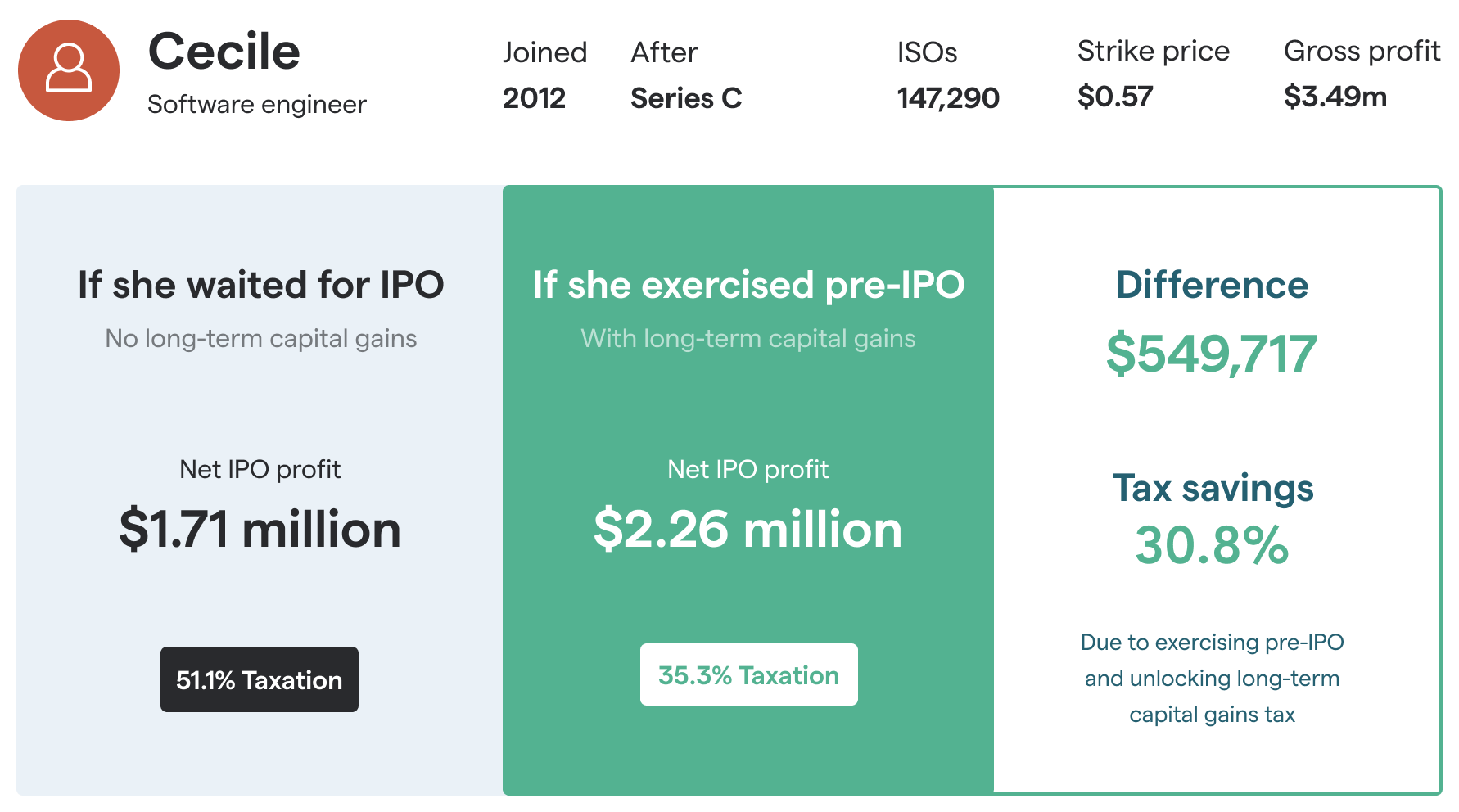

Cecile, an early software engineer at Pinterest:

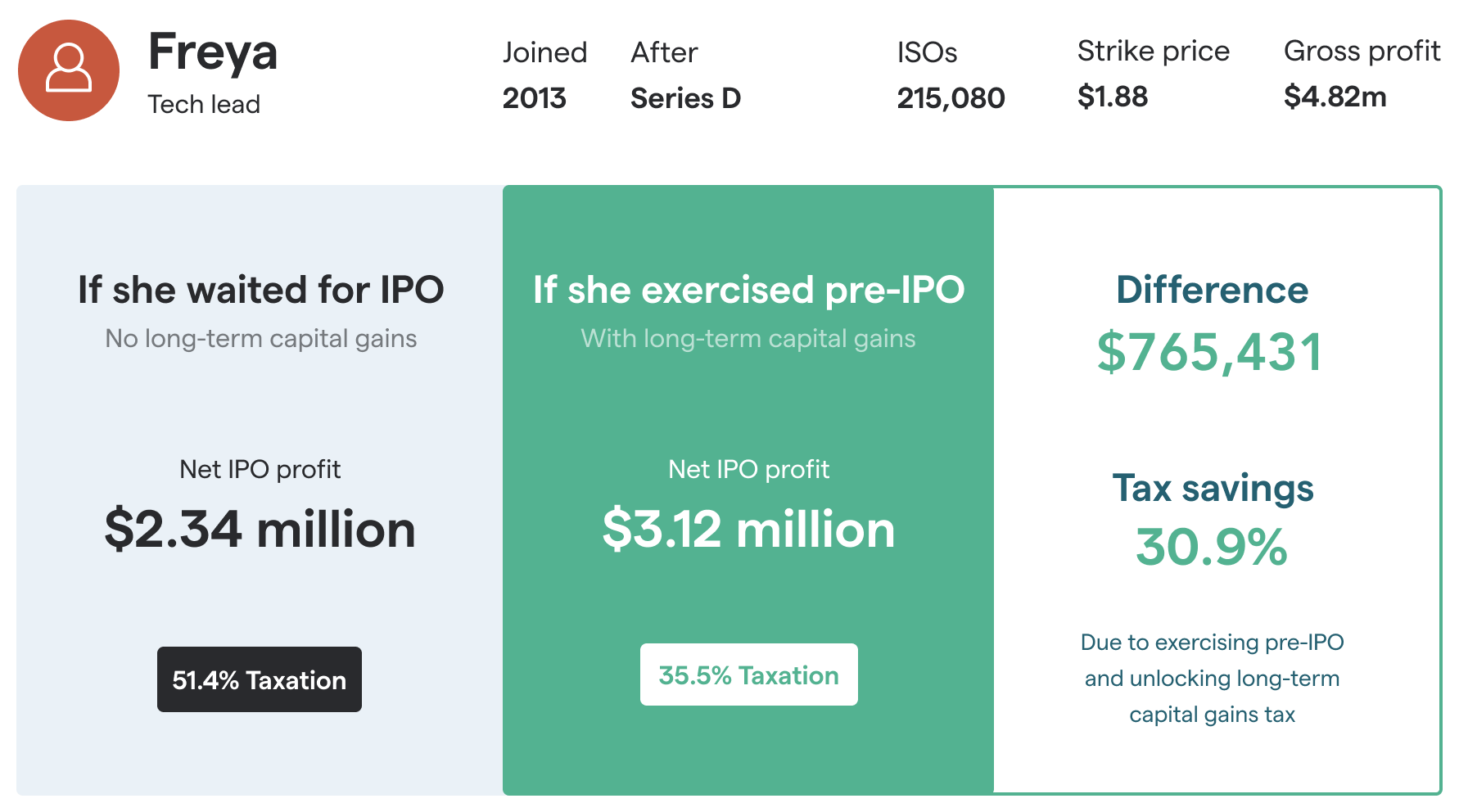

Freya, a Pinterest tech lead:

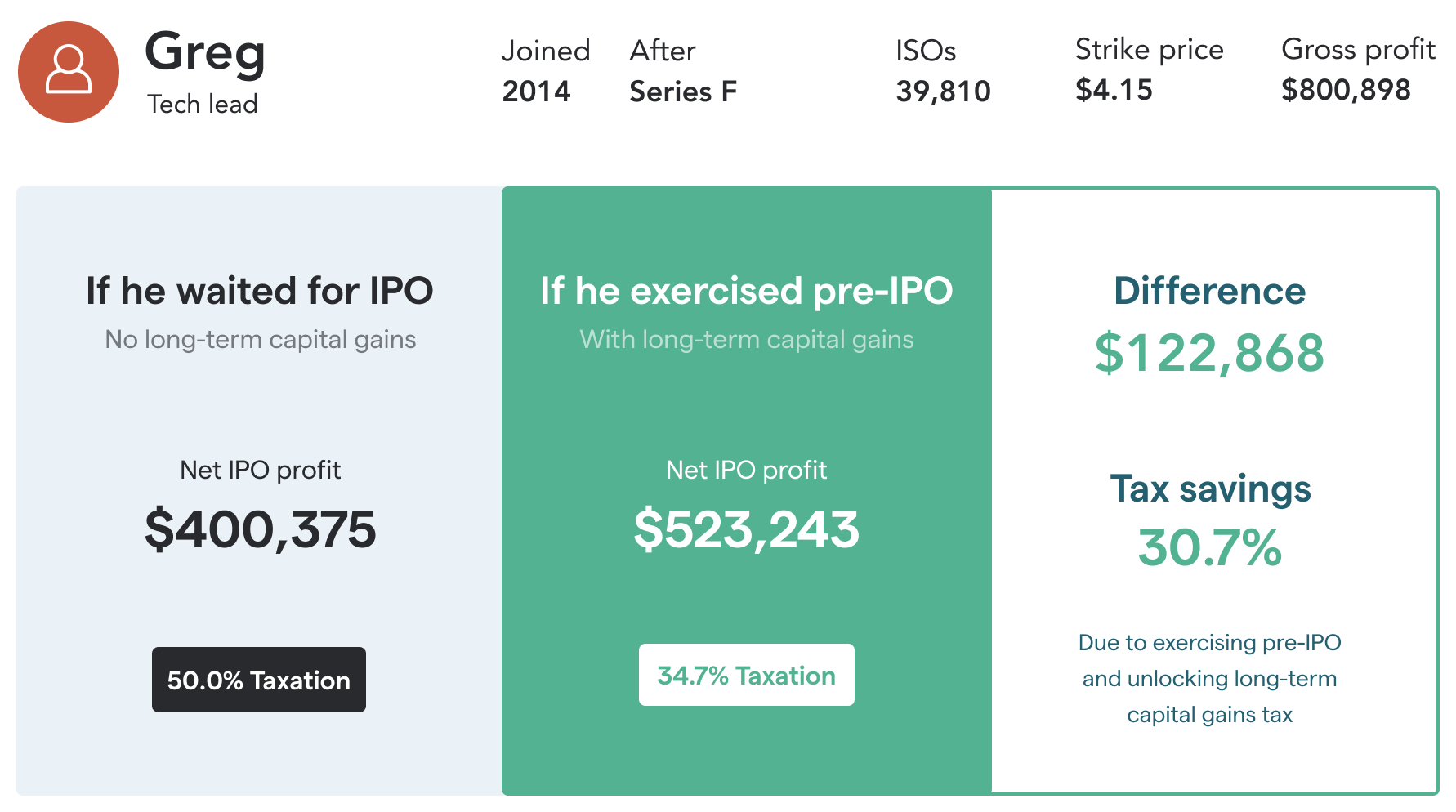

Greg, also a tech lead who joined Pinterest a little later:

Alright, some details on how to interpret this data. It's based on real people, but their names and numbers are anonymized. It's assuming they all sold their shares on the first possible day after the IPO, when the share price was $24.27.

Of course, the data may not be representative of how well other shareholders fared. There's no guarantee of future performance or success. In fact, some private companies may never even IPO or exit.

So what can you do with your startup stock?

If you're looking to unlock long-term capital gains, all you have to do is exercise your pre-IPO stock options. You just need to decide whether it’s worth it.

It’s a trade-off: you invest the costs of exercising today, so you can earn much more in the IPO.

To make the call, you’ll want to do a bit of financial planning. What’s the difference between long-term capital gains and what would it cost for you to exercise?

In summary, if you want to plan for the upcoming IPO, there are three steps:

- Calculate how much you’d benefit from long-term capital gains

- Calculate your total exercise costs

- Worth it? Then get in touch with your employer and exercise

Step #1: Calculate the difference for you

As you can see from the Pinterest examples, the specific numbers differ from person to person. It depends on whether you have NSOs and/or ISOs, their strike price, your personal details, etc.

What you want to know is the net difference: what would your IPO gain be with versus without long-term capital gains?

That calculation is incredibly complicated, so we’ve built a tool. We call it the Exercise Timing Planner. It looks like this:

Just sign up for a Secfi account to use the calculator. It’s free.

Step #2: See what your exercise costs are

Liked what you saw in step #1? Then you can exercise to start the 12-month clock for unlocking long-term capital gains.

But exercising stock options isn’t free, so you have to know what it’ll cost you.

Beyond the exercise price, exercising also comes with a tax bill. That’s because when you’re buying shares at a low price (which is what exercising is), you’re considered to be making a ‘phantom gain’ (assuming strike price < 409A valuation).

The tax you owe depends on many factors: your type of employee stock options, the current 409A valuation (also known as fair market value), your salary, etc. If you have ISOs, there's the dreaded and complicated alternative minimum tax.

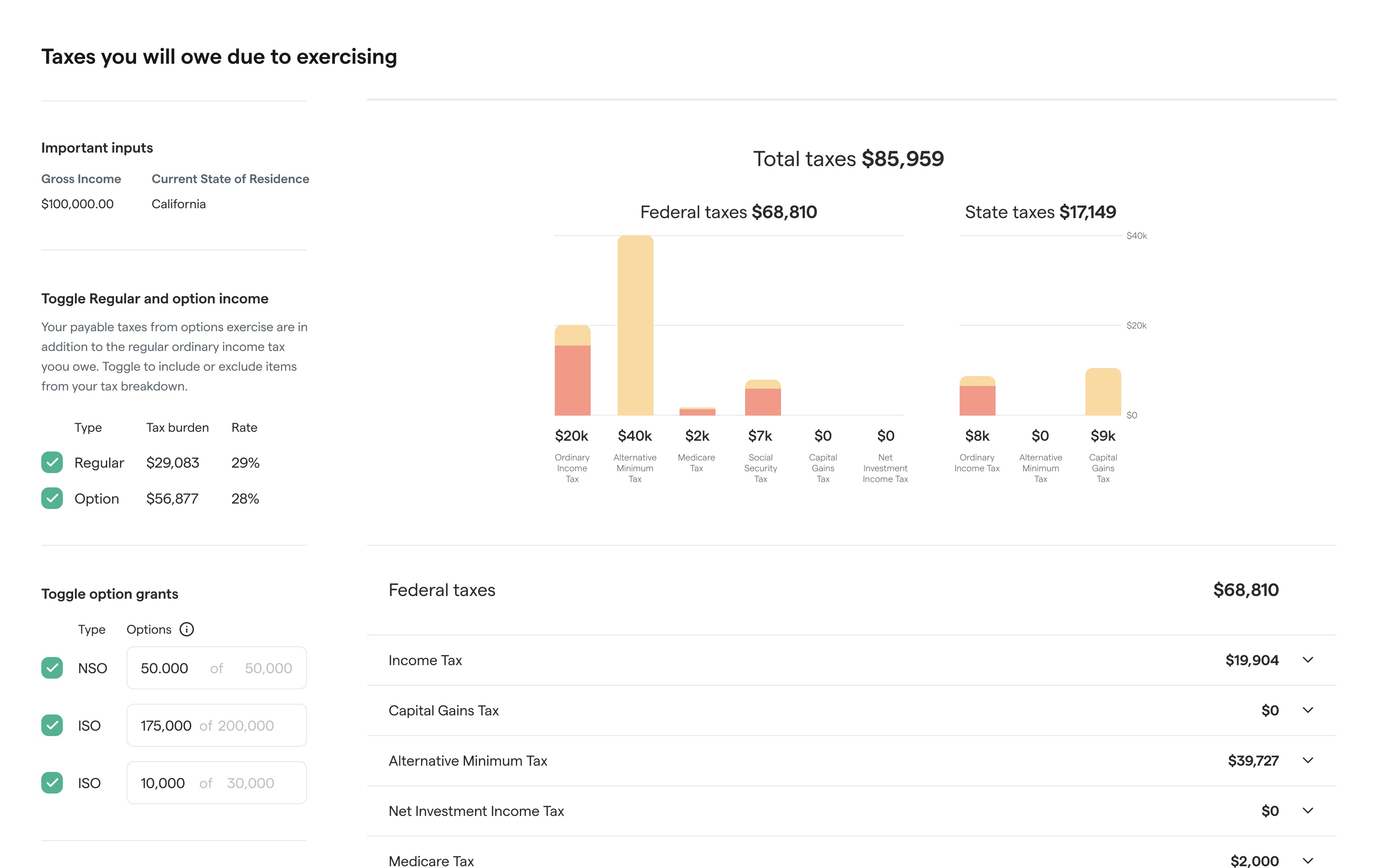

Another complicated calculation, so again we built a tool to crunch the numbers – the Stock Option Tax Calculator:

Just fill in your details and it'll spit out your total exercise cost, including taxes.

If you’ve already signed up in the previous step, the tool is two clicks away.

Step #3: If it’s worth it, consider exercising

Decision time. Are the tax savings computed in step #1 worth the upfront investment of paying your exercise costs as computed in step #2?

Then it could be time to exercise your stock options.

Here’s how to make sure you’re not missing anything:

- Get in touch with your employer, follow their process, and keep track of progress. Depending on how they organize things, exercising may take manual steps on their end that may not always be on top of their priority list. The sooner your exercise is official, the sooner the 12-month long-term capital gains clock starts.

- Take note of the tax withholding your employer is already doing for you. Compare this amount to your tax bill as estimated in step #2, and be prepared to make additional payments later in the year. Work with your financial advisor to be 100 percent sure on the amounts.

- If you are early exercising (meaning if some of the options you’re exercising haven’t yet vested, which is allowed at some startups), make sure to file a 83(b) election with the IRS within 30 days.

What if exercising is too costly?

Especially if you’re an early employee, the exercise tax bill can be hefty.

If this puts exercising out of your financial reach, there are two things you can do:

- Exercise only a part of your options

You can exercise options up to the amount you’re comfortable with paying for. This way, you still partially benefit from long-term capital gains. - Have Secfi fund your option exercise.

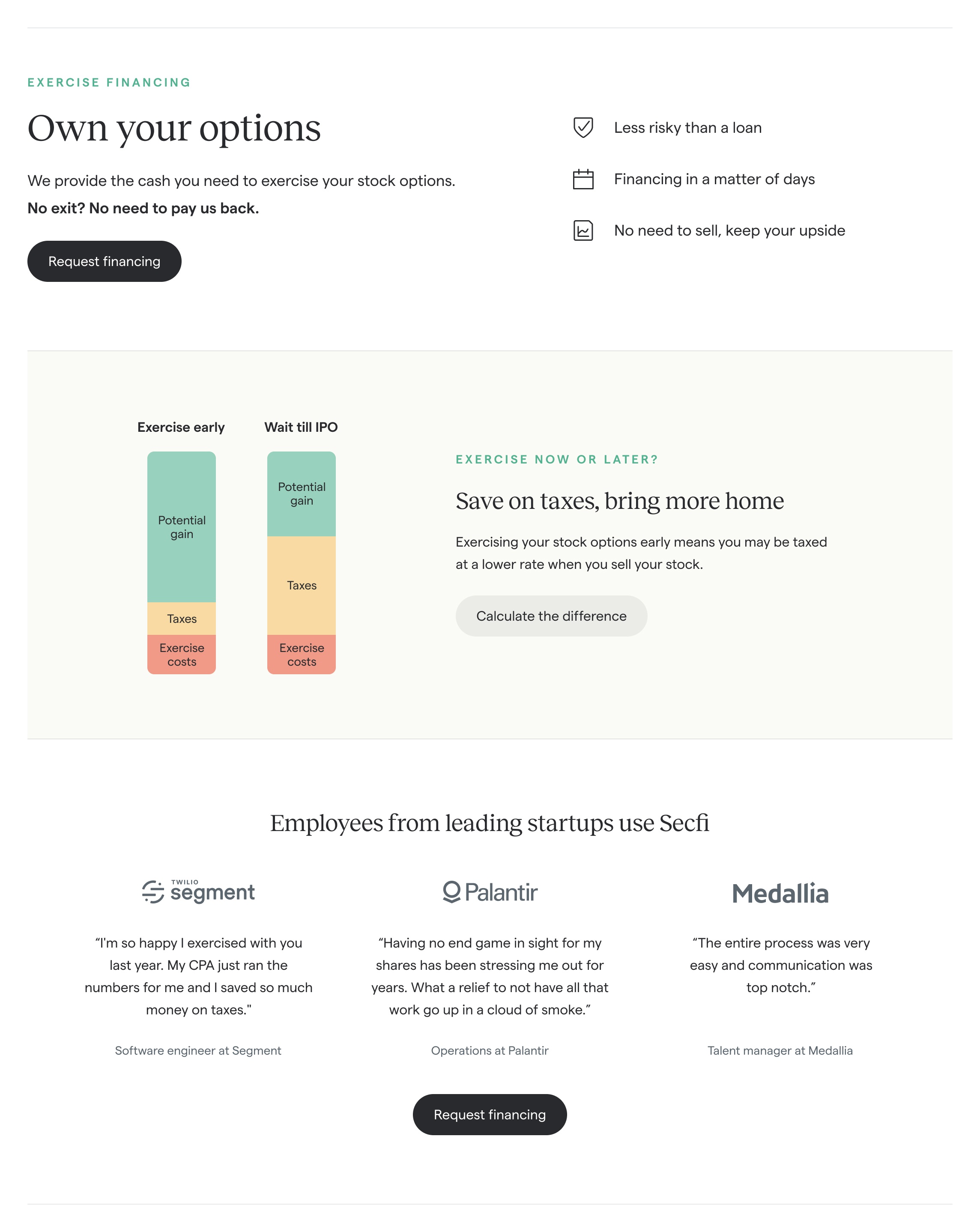

We provide non-recourse financing to cover your exercise costs. It’s low-risk: you only have to pay us back if your equity allows you to. If your company successfully exits, we share in the upside. If for some reason it doesn’t, Secfi takes the loss. Your personal money is not at risk.

Another solution is to do a mix of the two: exercise as many stock options as your personal budget allows, then have Secfi fund the remainder.

How Secfi Helps Fund Your Stock Option Exercise with Non-Recourse Financing

All our tools and calculators are completely free to use.

We make money by funding option exercises. Here’s how it works:

- We wire you money so you can cover the total cost of your stock option exercise – including all taxes such as the alternative minimum tax (AMT).

- If you’d like, you can add some liquidity on top. Extra cash for whatever you’d like to use it for.

- You only pay us back when there is an exit, such as your company going public or being acquired. That’s when you sell your shares and we share in the upside with you.

- If for some reason that exit never happens, you don’t pay us back. We’ll take the loss.

The financing is non-recourse, which means your stock in the company is the only collateral. In other words, your personal money is untouched – you’ll never have to pay back more than what your shares sell for in the exit.

Also, your shares remain in your ownership all the way to the exit. (Employers are often happy to learn about this particular feature of our product, because that means they won’t have to transfer the stock to anyone else).

Since 2017 we’ve done this for hundreds of employees across 80+ tech companies, in Silicon Valley and beyond.

For example, we've helped employees of:

2. Request exercise financing

3. We invite you for a ‘we answer all your questions’ call.

Our process is largely automated, but we've found most folks like to discuss financing with a human. It’s a significant decision after all.

Secfi's Equity Strategists have helped hundreds of startup employees maximize the value of their stock options, and they're ready to explain anything equity and IPO-related. (By the way, just use the chat below if you'd like to have a chat with them before signing up ↘️)

4. We send you a detailed financing proposal.

The proposal is catered to your details. It models out your specific scenario and shows your benefit.

This last step normally takes 2-3 weeks, as our investment team does a risk assessment of the company.

However, if you work for one of our pre-approved companies (that includes most unicorns) we can skip this step and you’ll have the proposal in just days. You'll automatically see whether your company is pre-approved when you sign up.

If you're interested in exploring financing, you can sign up and request a proposal here.

So how do long-term capital gains work exactly?

TL;DR:

- Selling shares you’ve owned for < 12 months is taxed as ordinary income

- Selling shares you’ve owned for > 12 months is taxed as long-term capital gains, partially or fully

- The specifics are complicated...

- ...but our Exercise Timing Planner tool happily crunches the numbers for you

The specifics:

Money you make with stock options is normally taxed as ordinary income. But under the right conditions, it’s (partially) taxed as long-term capital gains. That’s a lower tax rate, meaning your gains could be higher.

These ‘right conditions’ are as follows. For both incentive stock options (ISOs) and non-qualifying stock options (NSOs), if you’ve owned the shares for at least 12 months, the difference between:

- The 409A valuation at the date you exercise, and

- The sell price of the shares

gets taxed as long-term capital gains. In other words, to unlock the tax savings, exercise 12 months prior to selling.

The ‘other part’ of your pre-tax gain, however, will still be taxed as ordinary income. So that’s the difference between

- The strike price of your options, and

- The 409A valuation at the date you exercise

But that part you can get taxed as long term capital gains too, if:

- Your options are ISOs

- The sale is at least 24 months after you were granted the ISOs

- You’ve continuously been employed with the company since being granted the ISOs.

If that’s all the case, your sale is a so-called qualifying disposition and your full pre-tax gain – so that’s the price at which you sell your shares, minus the strike price you’ve paid – will be taxed as long-term capital gains. This is the most advantageous scenario.

Phew! The complexity of the U.S. tax code never ceases to amaze.

So that’s exercising more vs. fewer than 12 months ahead of selling. But what if you not only exercise less than 12 months prior to selling, but never exercise at all?

If you never actively decide to exercise, then when you sell your equity, what technically happens is you exercise your options at that moment. In other words, you buy and then sell the shares in an instant.

Since you don’t need cash to do it, this is also called a cashless exercise: you’ll cover the exercise costs with your sale payout.

Of course, with a cashless exercise you don’t hold the shares for 12 months (you don’t hold them at all) so your full gain is taxed as ordinary income ==> no tax savings.

How big is the difference between the long-term capital gains and ordinary income tax rates?

2020 federal ordinary income brackets for single individuals:

- 10%: $0 to $9,875

- 12%: from $9,875

- 22%: from $40,125

- 24%: from $85,525

- 32%: from $163,300

- 35%: from $207,350

- 37%: $518,400 and up

2020 federal long-term capital gains brackets for single individuals:

- 0%: $0 to $40,000

- 15%: from $40,000

- 20%: $441,450 and up

Then there’s state tax, maybe you’re married, there’s a so-called additional net investment income tax, and there are other complicating factors, so it’s hard to tell what your effective rate will be right off the bat.

That’s why we built the Exercise Timing Planner, which accounts for all of these complications.

In the Pinterest examples above, we’ve seen the following effective rates:

- Ordinary income: 50.0% – 51.4%

- Long-term capital gains: 34.7% – 34.31%

Your situation will be different, but that gives an idea of the potential difference.

If I need to hold the stock for 12 months, am I not already too late for the IPO?

Nope. Two reasons.

First, from the moment your company starts the IPO process, it’s still a while until you can sell your shares.

There will be several months from announcement to IPO. Then after the IPO, there is usually a 6-month lock up period during which employees can’t sell their stock.

So depending on how far your employer currently is in the process (just rumored to have plans, or IPO already formally announced) your situations looks like this:

Second, even if you still haven’t hit the 12-month mark by the time the lock-up period ends, the fact that you could now sell your shares doesn’t mean you immediately have to. You can wait until long-term capital gains applies.

Admittedly though, you’re taking a risk by doing this. If you wait, there is the possibility that the stock price falls in the meantime. In the worst case this decline negates the tax savings you’ve waited for.

Of course, it could also go up. But the stock price can take a hit when the lock-up period ends, because many shareholders start selling that day.

(Note that the situation is different if your company gets acquired instead of going public. In that case you don’t control when you’re selling, which could indeed be too early for long-term capital gains.)

What if I exercise and the IPO fails / doesn’t happen / disappoints?

This is indeed a risk you’re taking if you exercise prior to the IPO.

If you decide to exercise and later it turns out that either:

- Your company goes downhill and doesn’t exit at all, or

- Your company does exit, but the exit value is so low that your payout from selling falls short of what you paid to exercise,

then you’ve made a loss.

With ISOs, you may be able to recover some of it. Since the alternative minimum tax (AMT) likely constituted a good chunk of your exercise cost, you’re now left with AMT credit – a tax credit you can use in subsequent years.

With NSOs, you can take the loss as a 'capital loss' and reduce your capital gains tax in the future. You will also be able to reduce your ordinary income tax bill if you don't have capital gains – but that's limited to $3000 per year.

If you’d rather not take any risk, then exercise with Secfi financing. If in that case the IPO disappoints (or never comes), we take on the loss.

Is it better to pay for the exercise costs myself, or take Secfi financing?

The drawback of using Secfi financing to get long-term capital gains is that you share the upside with us. If the IPO is sufficiently successful, then that’s net still better than not having exercised at all (and getting the higher ordinary income tax rate).

But of course, the most profitable scenario is if you’d cover your exercise costs all by yourself – you’d benefit from long-term capital gains and wouldn’t have to share any of it.

For that reason, if you’re OK with taking on some risk you could go for the in-between option:

- Determine the amount of money you’d like to invest yourself

- Exercise as many stock options as that budget allows you to

- Exercise the remainder with Secfi financing

When you request a financing proposal, we’re happy to include such a scenario. We’ll model out for you the impact of bringing various amounts of money to the table yourself vs. having us fund the exercise completely, so you can decide.

A word about secondary markets

One alternative to taking exercise financing is selling pre-IPO shares to a third party. This can either be as part of a company-organized tender, or by finding a buyer yourself. This is known as a secondary sale or as selling on secondary markets. (It's called like that because no new company shares are created. The buyer gets second-hand shares.)

You can either sell just enough of your equity to cover your exercise costs, or sell all of it to take out cash prior to the exit.

The downside is that by selling, you let go of your ticket to the IPO. You receive the dollar amount you sell for and that's it. With exercise financing your equity stays yours, so you can take out cash before the IPO and potentially make additional money after a successful exit. In other words, you keep the potential upside.

Of course, a lot depends on the specific price you're able to sell for versus the rates at which you can get exercise financing. If you're considering selling and would like to compare with exercise financing, just let us know in your request and we'll include both scenarios in our proposal.